The Union of 1707 created the commercial environment crucial for economic expansion. By 1750, imports from the Chesapeake region to Scottish ports were greater than the total of the largest English outlets, including London.

From 1740 until 1790, Glasgow stood as the unrivalled trading centre of Britain. It became a global economic force by monopolising the trade in tobacco and, to a lesser extent, the market in sugar. Glasgow became a vast warehouse for imports which were re-exported to Europe and in particular to the French market. It revelled in its new role as the key entrepôt of the produce of chattel slavery to meet European-wide demand.

This economic powerhouse was dominated by men who were

“Devoted to commerce: men concerned with fine calculations of profit and loss, men of wide horizons, whose attitudes communicated themselves in various ways throughout their societies.”1

It was more than the new opportunities of access to the English colonies that propelled the tobacco and sugar trades. Glasgow’s merchants possessed a ruthless mindset underpinned by a strong sense of economic rivalry.

From 1740, a new generation of tobacco lords established themselves who dominated Glasgow’s civic and commercial affairs. Most came from traditional mercantile families, but some of the most prominent were incomers. John Glassford (1715-83) hailed from Paisley, William Cunninghame (d.1789) was from Ayrshire and Alexander Speirs (1714-82), ‘the mercantile god of Glasgow’2, came from Edinburgh.

It was only natural that these men, when they made their fortunes, sought to acquire townhouses in the commercial heart of the city. Glassford, one of the most wealthy and influential of the tobacco lords, purchased the Shawfield Mansion in 1760. When he died there in 1783 he was £50,000 in debt, ruined by his love of gambling and his losses in America.

Alexander Speirs’ story illustrates the kinship networks and connections crucial for colonial trading success. He married May Buchanan and became a leading partner in many of the Buchanan family interests. He purchased The Virginia Mansion in 1770 and, unlike many, died with his fortune still intact.

In 1778, William Cunninghame built the opulent Cunninghame Mansion, now at the heart of Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art.

This triumvirate of tobacco lords reached the pinnacle of mercantile success and wealth not only in Scotland but Great Britain. Their success was based on a set of business practices, known as the store system, as well as the ruthless expansion of slave labour in the Chesapeake.

The storage method used by Glasgow merchants was new, specifically designed for tobacco purchasing. Permanent stores were built across rural Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina which allowed factors to purchase tobacco direct from the planters. Each store was a self-sufficient enterprise run by factors who were usually young Scottish apprentices. Indentured servants were used as clerks and black slaves did the manual work. The tobacco was usually traded for manufactured goods exported across the Atlantic and advanced on credit to the planters.

The store system ensured that planters delivered the best tobacco at harvest time. It had, in turn, a significant influence on the development of chattel slave plantations in North America. This extension of credit from the West of Scotland, the only source of essential goods available to smaller plantation owners, allowed them to purchase more transported Africans in order to increase tobacco yield. Although the store system meant that factors dealt primarily in tobacco collection and trading goods, it was symbolic of the hands off role of Glasgow in the business of slavery. The city was economically dependent on chattel slavery yet at the same time far removed from its brutal realities. This helped create a myth of detachment and non-involvement.

In Glasgow itself, the colonial trade and the store system underpinned the dominance of the tobacco lords. It also had a series of other effects. The most obvious lay in the growth of the city’s infrastructure – both on the Clyde and in nearby streets. The river’s shallows were dredged from 1768 onwards, the work of the engineers Golborne, Smeaton, Rennie and Telford, so that at least six feet of water reached the harbour at the Broomielaw. The harbour itself was further developed in 1770 as part of the same undertaking.

The genesis of Jamaica Street, named after the largest slave plantation in the Caribbean, is telling. In 1756, the firm of Richard Oswald and Co., owned by the kin of the slave entrepreneur who had acquired Bance Island a few years before, applied to the Town Council regarding the purchase of land surrounding its bottle works at the Broomielaw, first established in 1730. It was no surprise that the name of Glasgow’s premier sugar producing island was given to this street which became an important thoroughfare for colonial traders on the way to their warehouses.

Jamaica Street was opened in 1763 at the height of mercantile success. It rapidly became one of Glasgow’s busiest streets, devoted to colonial commerce. In a short space of time a shipping office, a sail-cloth company and a customs house arrived.

The store system stimulated a series of spin-off trades. A new urban economy was developed as small manufacturers set up factories in and around the Trongate. In the period between 1700 and 1815, around ninety factories, such as leather works, glassworks, breweries, potteries and makers of sail cloth and ropes were established with some form of financial aid from colonial merchants.

Glasgow’s textile industry also to some extent expanded due to colonial investment. The West Indian supply of cotton ensured the wheels were spinning to produce linen, wool and silk for re-export. From 1750 until 1775, most of these exports went to America and the Caribbean. The slave islands became both the primary producer and the export market of a rough ‘slave cloth’ which became the basic attire of many transported Africans. The cotton was grown by slaves, shipped across the Atlantic by merchants such as Alexander Houston and Co., woven in Glasgow factories and then exported back – an extension of the city’s highly profitable role as an entrepôt.

Colonial investment also provided a good deal of the impetus for the development of the coal and iron industries in the West of Scotland. The early ironworks were established largely to produce small wares – such as nails, spades, axes, anchors and hoes for export to America and West India. In the later period, colonial merchants invested in pig iron, and eventually coal mining ventures in Monklands and Ayrshire. The profits from chattel slavery seeped into the economy of the West of Scotland by a variety of routes.

The role of the colonial trade in re-aligning the Scottish economy remains a contentious issue. Only part of Scotland’s industrial revolution – and some would say quite a small part – can be directly or even indirectly attributed to the profits of slavery and its spin-off industries. In 1771, at the zenith of the tobacco trade, only just over a quarter of the value of the goods exported to the colonies came from Scottish industry.

Scottish merchants developed a sophisticated international trade network to source items to supply the American planters. Much of the exported linen, for example, came from Germany and Ireland. Large supplies of iron and wood came from Scandinavia. This commercial network produced profit at each end of the transaction: from the tobacco and sugar trade in Europe and from the supply of finished goods to the New World.

If there is some doubt about whether the colonial trade produced an industrial complex in the West of Scotland or merely a warehouse economy, a close connection certainly developed between transatlantic trade and the growth of financial institutions. Banks were used to fund the tobacco and sugar trade and plantations, in addition to the private investment of individuals and institutions.

The first banks in Glasgow – the Arms Bank (1750), the Ship Bank (1750) and the Thistle Bank (1761) were all directly funded by tobacco lords. The Ship Bank was situated in the then commercial centre of Glasgow, at the corner of the Briggait and the Saltmarket. The building which housed the Ship Bank had been built as early as 1640 by Provost Bell and was typical of the period with three storeys. That building is gone although the Old Ship Bank, a pub, stands in its place.

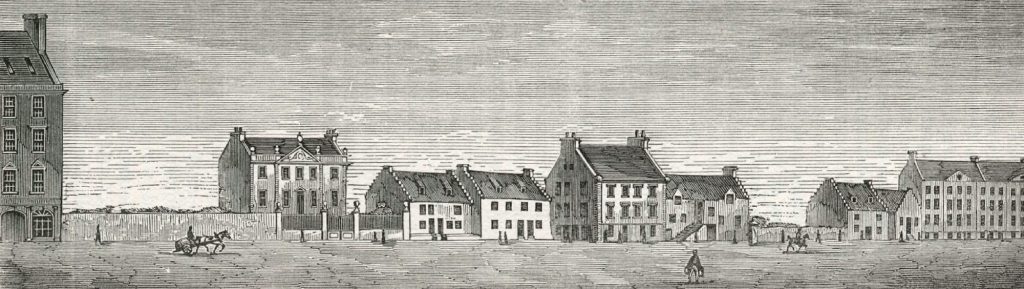

The new industries were mostly located to the east, often close to the water courses on the fringes of the old town. As the population increased in the heart of the original medieval settlement and the Town Council invested in a series of grandiose buildings there, merchants sought to escape the overcrowded conditions by building their residences to the west. Between 1750 and 1775 twelve new streets and squares were laid out.

Trongate, named after the old public weigh beam or ‘tron’ at its east end, was one of the original eight streets in Glasgow. This area is close to the Merchants Steeple, where the colonial traders would look down to the Broomielaw to catch a glimpse of the returning ships, laden with cargoes from Virginia and West India. The goods were weighed at the Tolbooth on their way to storage before re-export – part of the warehouse economy.

The tobacco lords, resplendent in their scarlet cloaks, gold tipped canes and flowing wigs, liked to convene in Trongate, which became known as the Plainstanes, the first paved street in the town.A new etiquette was devised for the nascent nobility who paraded along the Plainstanes:

“For one of the shopocracy to speak to a tobacco aristocrat on the street, without some sign of recognition from the great man, would have been regarded an insult. They were princes on the pavement and strutted about every day as the rulers of the destiny of Glasgow”3,

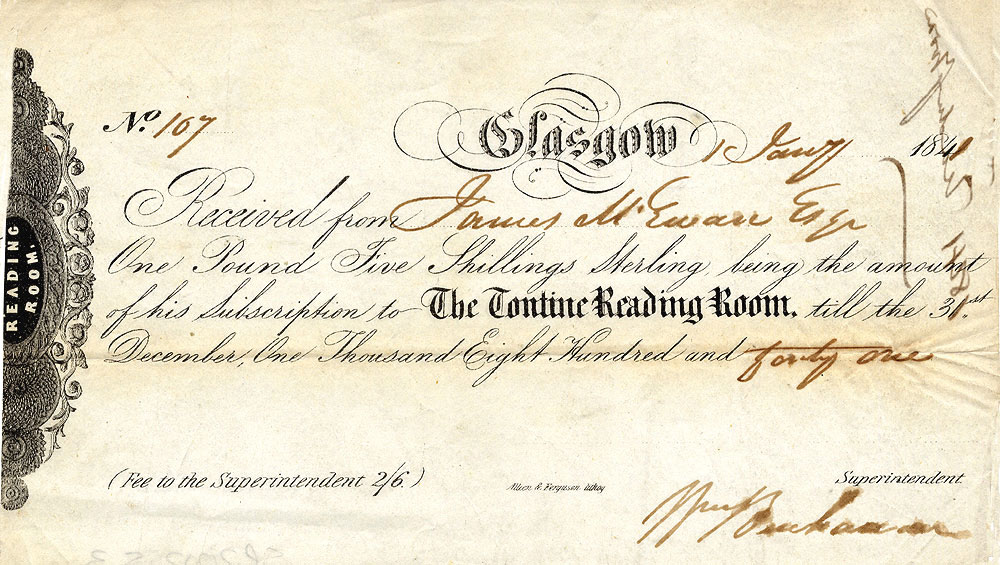

The area soon became the social and commercial headquarters of Glasgow. Colonial profits built in the Tontine Rooms in 1781 to a design by William Hamilton. ‘The Tontine Society of Glasgow’ was formed by the mercantile elite, such as William Cunningham of Lainshaw (d.1789), George Buchanan, Robert Bogle of Daldowie (1700-84) and John Glassford (1715-83).

The famous Tontine Heads, most of which survive to this day at Provand’s Lordship, were placed above arches and faced directly onto the Plainstanes. The Tontine society raised between £5,000 and £6,000 to build the Tontine Rooms, which included a hotel, coffee room and an assembly hall. Conversation was doubtless dominated by harvests in the Chesapeake, tobacco prices in Europe, growing conditions in the Caribbean and the price of slaves in Africa.

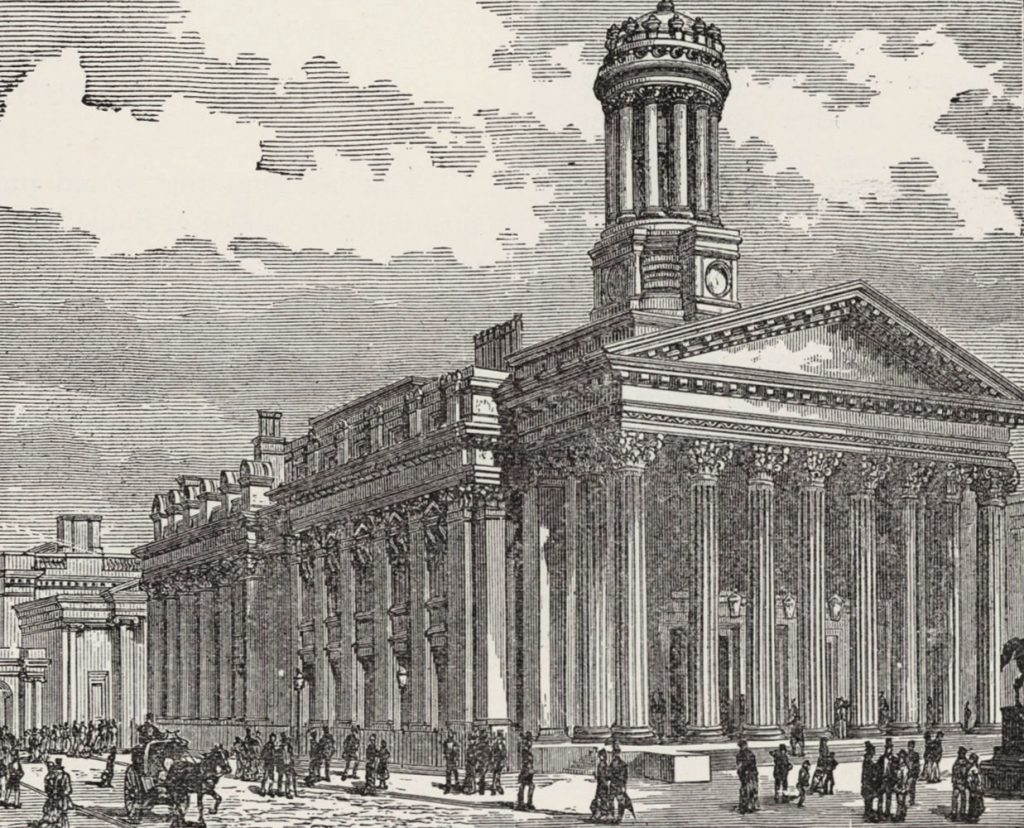

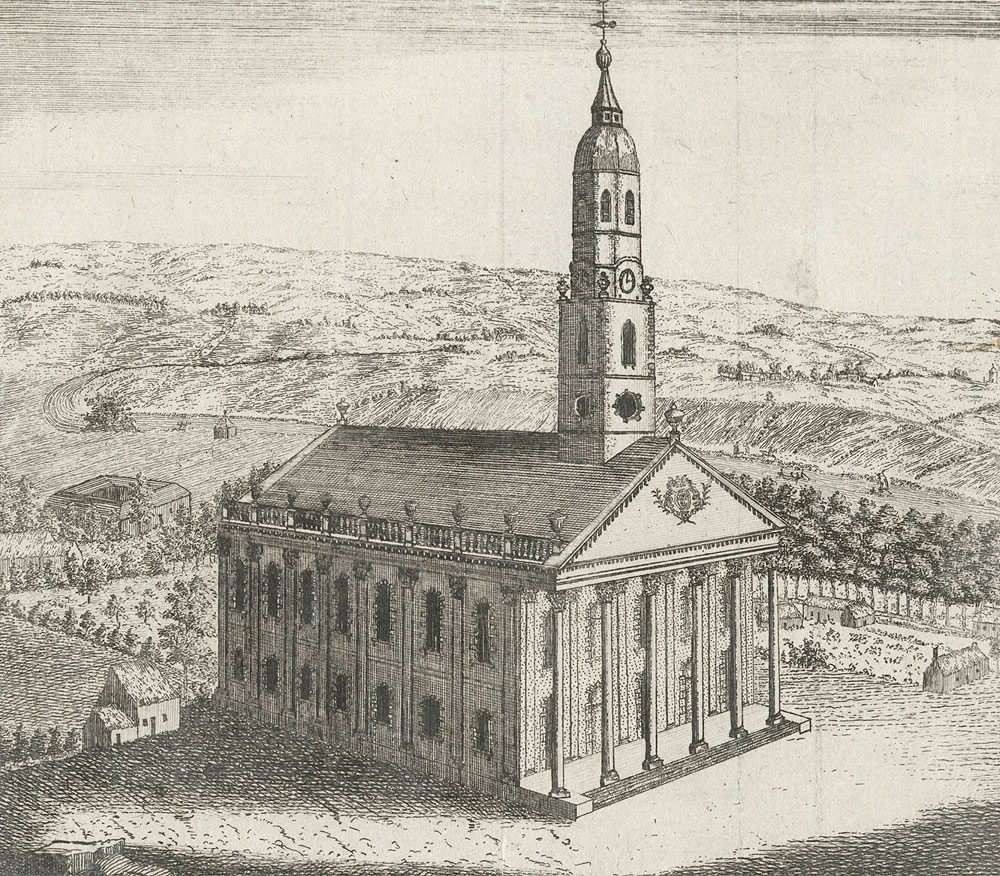

The spiritual needs of the new urban population to the west of the old town led to the construction of St Andrew’s Church between 1739 and 1756. The cost was £15,000 to £20,000, a huge sum (around £3 million in modern terms). An Act of Parliament in 1768 suggested that this cost was met by the merchant dominated Town Council,

“Whereas, by the great increase of inhabitants in the City of Glasgow, an additional Church became necessary, which the magistrates and Council of the said city have, at considerable expense, Erected and Built accordingly, and it is called, or known by the name St Andrew’s Church.”4

When the colonial merchants worshipped in St Andrew’s, its interior was an extravagant display of mercantile wealth. The lustrous Spanish mahogany furnishings were imported from the West India plantations. The building itself was laid out to plans by Allan Dreghorn, modelled on St Martin-In-The-Fields in London. Its impressive steeple is almost identical to St Martin’s. Raised on a plinth so that visitors ascend to its six columned portico, St Andrew’s is undoubtedly among the finest examples of ecclesiastical architecture in Scotland. The building, no longer used for worship, is today returned to its former glory after being restored by Glasgow Building Preservation Trust.

In 1787, the area around St. Andrew’s was laid out in a square of three-storey townhouses, described as ‘perfect examples of elegance and splendour for the use and resort of Merchants and others’5. For a time St Andrew’s Square became, along with Virginia Street, one of the most fashionable and expensive places to live in the new Glasgow. But its status as the headquarters of the Merchant City was short-lived, as it lay too close to the stench and squalor of the overcrowded medieval town. Its wealthy inhabitants took flight further westward.

The early urban form of the Merchant City was set by the alignment of the Shawfield and Virginia mansion grounds, which ran perpendicular to the Trongate. These were followed by the development of Miller Street in 1762, Queen Street and Buchanan Street in 1765 and Ingram Street in 1772, creating a grid resembling a tooth comb.

Miller Street was named after John Miller of Westerton, a land speculator who first laid out the street in plots in the 1750s. A variety of merchants set up residence there. Plot 6 was acquired by Robert Hastie, ‘an extensive American merchant’, in May 1772. After Hastie’s firm ‘Robert and William Hastie’ failed, like so many others in the 1770s, the land was sold to John Craig, a wright, who constructed what is now known as the ‘Tobacco Merchants House’ at 42 Miller Street.

Craig’s relatively modest dwelling was subsequently occupied by other prominent merchants such as Robert Findlay of Easterhill (1748-1802), a tobacco importer who lived there from 1780 until his death. A small-scale interpretation of the architectural style which produced the Shawfield Mansion, it is the only house of its kind to survive in the Merchant City. It illustrates the living conditions of ‘average’ merchants in the eighteenth century – sometimes called the tobacco lairds, in contrast to the grander Palladian mansions of the wealthier tobacco lords.

The most prominent tobacco family of all left a lasting legacy in the centre of Glasgow. Buchanan Street, arguably the most potent symbol of the modern cosmopolitan city, is named after the tobacco lord, Andrew Buchanan (1725-1783) nephew of Buchanan of Drumpellier, the founder of the great Virginia dynasty. The Buchanans enjoyed considerable wealth and social status in eighteenth-century Glasgow. Andrew was a partner in both Buchanan, Hastie and Co. and Andrew Buchanan and Co., two of the most powerful Virginia trading firms, (although both folded in 1777 due to financial difficulties).

Andrew Buchanan purchased the land, which would subsequently become the eponymous street, in 1760, and lived there for a number of years. A sharp increase in land values in the area resulted in speculative development of a series of small plots and the building of high tenements which transformed its character. The first tenement in the area was built in 1774. It is ironic that the street, originally sold off in low value plots due to its distance from the business end of town, is now at the very centre of the city and the wealthiest in Glasgow.

Colonial wealth came and went, mostly in the traumatic years of the 1770s. But the link between commerce and industry remained, underpinning the burgeoning townscape. The relationship between the two was confirmed with the establishment of the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce in 1783. In the streets of the new town, private mansions, ornate churches and grand civic buildings all testified to the extent of the profits of trade with the New World. So, too, did a striking number of prestigious rural landed estates.

Next section:

References

- Walt Whitman Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth, 1960 p31.

- T.M. Devine, The Tobacco Lords: A Study of the Tobacco Merchants of Glasgow and their Trading Activities, 1740-1790, 1975.

- G. Stewart, The Buchanans of Drumpellier and Mount Vernon in Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, 1881.

- J.F.S. Gordon, Glasghu Facies: a View of the City of Glasgow- Vol. 2, 1872 p572.

- J.F.S. Gordon, Glasghu Facies: a View of the City of Glasgow- Vol. 2, 1872 p573.