From 1787 onwards, the powerful philosophical and legal opposition to slavery in the British colonies was followed by a political challenge in the British Parliament. This did not take the form of an outright attempt to abolish slavery in the colonies; it had the more modest aim of ending the maritime trade in transportation.

Even so, the campaign can claim to be the first human rights crusade in British history, with an unprecedented mobilisation of public opinion and support. It became a truly national movement as petitions, indicating popular opposition to the slave trade, were sent to Parliament in 1788 and again in 1791 from towns and cities across Britain.

The campaign began with the founding in London of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787. Following the legal precedent set by the Somerset case in 1772, a small group of Quakers initiated a public campaign that would lead to the destruction of one of the foundations of the British Empire. Strong leadership combined with ingenious mobilisation tactics to promote the cause for abolition. This group used unprecedented propaganda to exert extra-parliamentary pressure and co-operated with William Wilberforce (1759-1833), who led an abolitionist lobby in Parliament. Public meetings were held and newspapers printed lurid material to stimulate public concern. An Abstract of Evidence (1791) largely collected from the major slave ports of Liverpool and Bristol by Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) printed the first eye-witness accounts of the slave trade. The brutal abductions in Africa, the horrific conditions of the Middle Passage and the terrors of slave auctions in the colonies were illustrated in graphic detail.

The scope of challenges to the slave trade widened beyond philosophical and Christian moral arguments to the practical and the economic. The argument that the trade was a necessary evil which was needed to underpin the British economy was confronted. The case put forward by vested interests, that the slave ships provided much-needed training at sea, was met by evidence showing the high mortality rates of sailors as well as slaves on the Middle Passage.

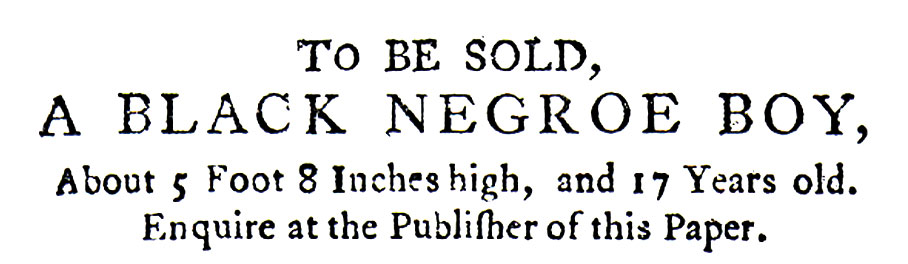

In Scotland, the philosophical challenge to slavery was followed by a propaganda campaign in newspapers. The Glasgow Advertiser printed evidence about the abductions of Africans from the west coast of Africa in 1788. Civic institutions also took up the fight and, by 1788, several had petitioned Parliament. Also in 1788, three professors at Glasgow University – John Millar, John Young and Patrick Wilson – were instrumental in persuading its Senate to back one of the first petitions from Scotland.

It is thought that Millar (1735-1801), a Professor of Law composed the 1788 petition. A committed abolitionist, he had continued the Hutchesonian tradition in his Observations Concerning the Distinction of Ranks in Society (1771) in which he proposed equality for all men. In this major work, he illustrated both the immorality of slavery and its unprofitability. He highlighted the hypocrisy of those who benefited from slavery yet also considered themselves liberal gentlemen.

The Church of Scotland also played a crucial, if sometimes ambiguous, role in the abolition movement. In Glasgow, the presbytery and synod petitioned Parliament in 1788 and again in 1791. It was one of forty presbyteries which did so.

The Kirk provided a focus for the local community, especially in rural regions, as enlightened thought boomed from pulpits to form a powerful theological rebuttal of the slave trade. Yet, although there was strong support for abolition amongst most of its ministers – far more so than in the Church of England – the Church of Scotland chose not to petition as a national body, perhaps because of a reluctance to be seen directly interfering with the legislative powers of Parliament.

By the late 1780s the national campaign began to achieve some momentum. A series of petitions sent to Parliament were signed by an estimated 60,000 individuals. Sixteen of the 101 petitions to Parliament came from Scotland. In February 1788, an inquiry was launched by the Prime Minister to examine the slave trade, whilst the Dolben Bill was passed which ‘improved’ conditions for slaves in the Middle Passage. Otherwise, the period was marked by deliberate delays rather than real concessions.A Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was resoundingly defeated by 163 votes to 88 in 1791.

The London Society continued collecting evidence of the brutalities of the slave trade and this was later distributed by some remarkable men. Thomas Clarkson travelled over 35,000 miles across Britain in the late 1780s and early 1790s. He visited Glasgow, where a dinner was held to honour him, although he did encounter some hostility in Scotland.

William Dickson (1751-1823), a London Scot who originally came from Moffat, made a gruelling three-month tour of Scotland on behalf of the London Committee in 1792. It was largely due to his efforts that Scotland sent 185 petitions to Parliament – more than a third of the British total of 519 – in the same year. Dickson, like so many of his generation, had worked for a time in the Caribbean. He had served for thirteen years as secretary to the Governor of Barbados where he was horrified by plantation conditions.

Dickson’s personal account of the horrors in the Caribbean did much to educate the public and illustrated the hypocrisy of the Scottish involvement in the slave trade. His innovative propaganda included distributing large numbers of pottery cameos produced by Josiah Wedgewood showing a kneeling slave in chains with the inscription ‘Am I not a man and a brother?.’1

The importance of petitions in the abolition campaign cannot be overstated. In 1792, petitions carrying over 400,000 names were sent from all corners of Britain to Parliament – an unprecedented demonstration of public feeling. It reflected a national campaign co-ordinated by elite leadership, and organised locally by provincial anti slavery societies.

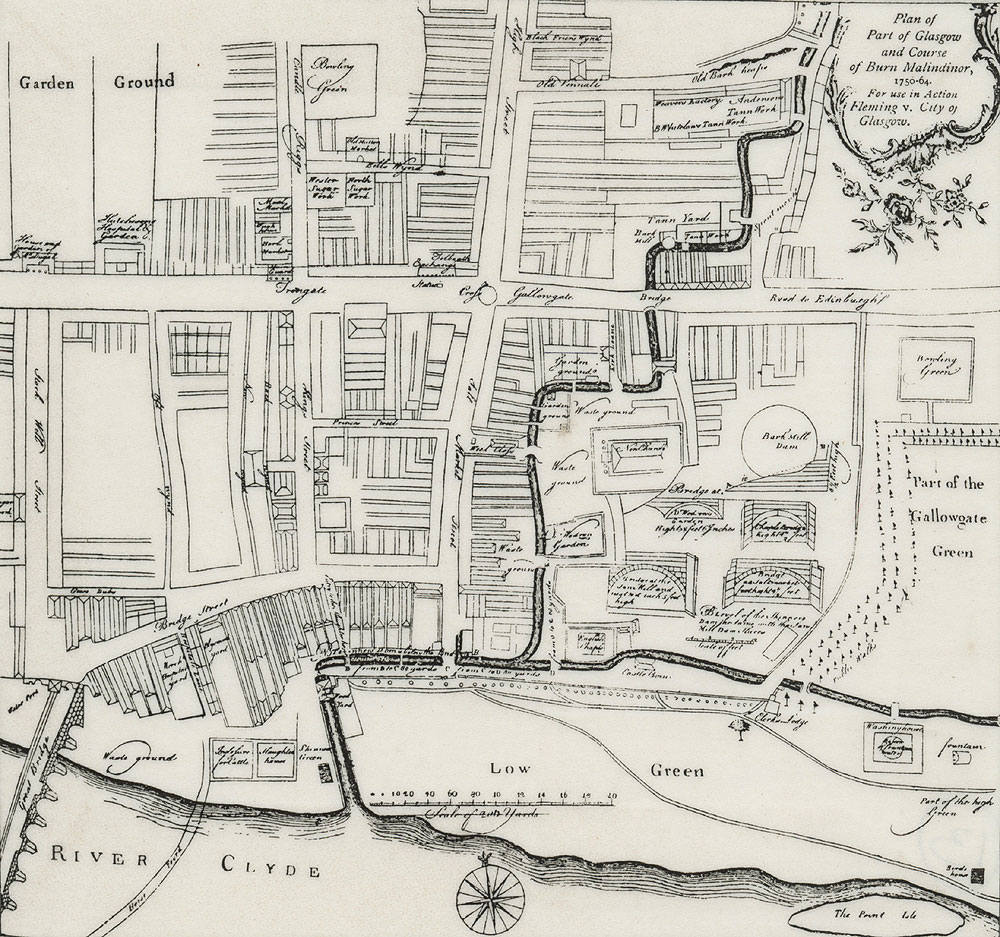

The London Society cultivated links across Britain with smaller, yet equally effective anti-slavery groups. By 1792, there were five abolitionist societies in Scotland, in Paisley, Aberdeen, Perth, Edinburgh and Glasgow. Numerically, the Edinburgh Committee was the strongest group. The Glasgow Society was vociferous but lacked structure and order, as William Dickson found out when he visited it in 1792. It held a public meeting in Anderston in February 1792:

“A respectable number of the inhabitants of this village convened to consider the proposal for the Abolition of the slave trade. Sensible of their own invaluable privileges, they may reflect with much sorrow on the wretched condition of millions of their fellow creatures, children of the same father, and members of the great same family, whom the vilest and most barbarous oppression have doomed to the cruellest of servitude and sufferings.”2

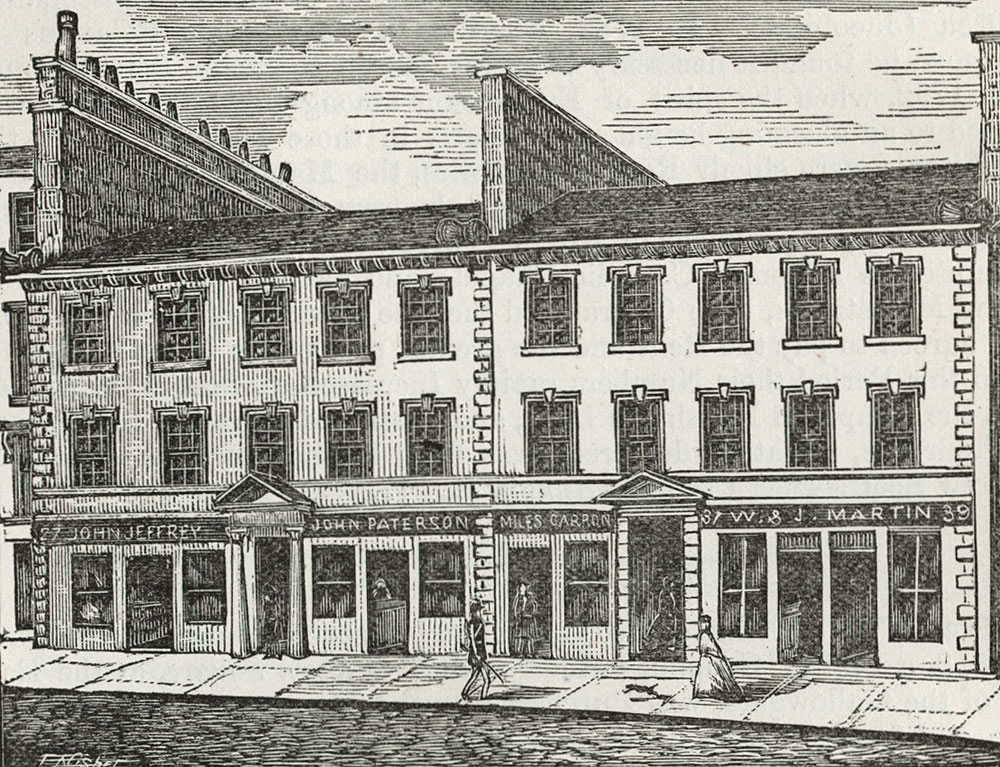

The meeting unanimously resolved to call for immediate abolition and to continue with the policy of co-operation with local societies and ‘the nation at large’. The proceedings of such meetings were regularly published in London and Glasgow newspapers. Clarkson’s Abstract of Evidence, produced in pamphlet form, became a key weapon for both the Glasgow and Edinburgh societies. To ensure its wide distribution, ‘a trivial price has been agreed’3. It was sold for a penny in the form of a twenty-four page pamphlet in shops in Glasgow. A supplementary pamphlet to encourage the public to boycott West Indian sugar and rum was sold for a halfpenny.

In Glasgow, abolition petitions were produced by the Glasgow Society, the University of Glasgow, the Trades House and the Society of Weavers but the same fervour was not matched in the city’s leading institutions. This is hardly surprising considering the influence of the powerful West India merchants. Influential bodies such as the magistrates refused to support the cause. There were no abolitionist petitions from the satellite ports of Port Glasgow and Greenock. Scare tactics were used, linking the threats of the overthrow of order in Europe to the abolition movement.

Fear of political and social upheaval in Britain after the French Revolution in 1789 was widespread. Wilberforce had publicly to deny connections with the Jacobin Club of Paris. The boycott campaign was branded by some in Glasgow as ‘treason’ since it would strengthen the economy of revolutionary France.

In 1791, newspapers sympathetic to the West Indian interests, such as the Glasgow Courier, printed graphic details of the slave revolt in St Domingue, now Haiti, alleging widespread murders of plantation owners. Vested interests in Glasgow also used more subtle tactics to limit the petitioning. The Glasgow Society was forced do deny a rumour that petitioners had to make a ‘pecuniary contribution’ when signing the petition.

The plethora of underhand tactics employed by the anti-abolitionists failed. An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was passed in Parliament in April 1792. However, amendments proposed in 1792 and 1795 by Henry Dundas, the ‘uncrowned king of Scotland’ for gradual abolition ensured a delay of a further fifteen years.

It was ironic that the same Henry Dundas who had made an impassioned appeal as Lord Advocate for the release of Joseph Knight in 1778. Now Secretary of State for Britain and the Colonies, he ensured that national vested interests and plantation economics took precedence over moral ideals. In spite of the delaying tactics, The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was given the royal assent on 25 March 1807 and the slave trade was outlawed. Slavery itself persisted for another twenty-six years.

Next section:

References

- Quoted in Iain Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery, 1756-1838, 2007.

- The Glasgow Courier, 21 February 1792.

- The Glasgow Courier, 25 February 1792.