The Union between Scotland and England removed the political and legal barriers that had limited colonial opportunities for Scottish merchants in the previous century. Some trade with the American colonies and even with Africa had existed previously, much of it illicit or clandestine, but a new era of opportunity arrived in 1707 with the opening up of a variety of commercial outlets.

A few Glasgow merchants had already figured in the slave trade, such as John Spreul who in 1705 proposed slave trading voyages from Scottish ports to the ‘Negroes Coast’1. But it was Union which legitimised the traffic in human misery.

The economics of slavery was based on the ‘Triangular Trade’2, which became one of the foundations of the British Empire. Ships left Great Britain, laden with goods exchanged for human cargo which in turn purchased goods for the homeward leg. At no stage were their holds empty, to maximise efficiency and profitability.

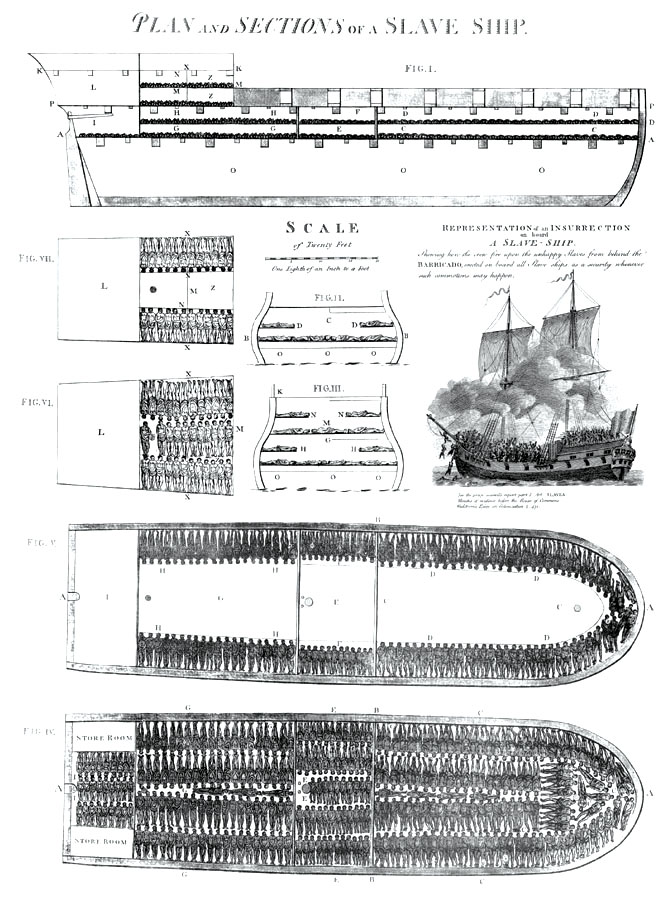

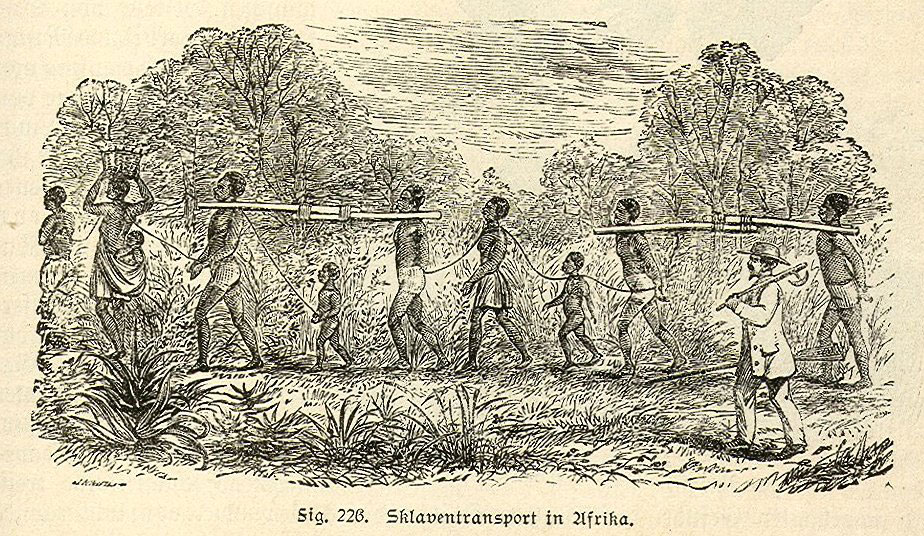

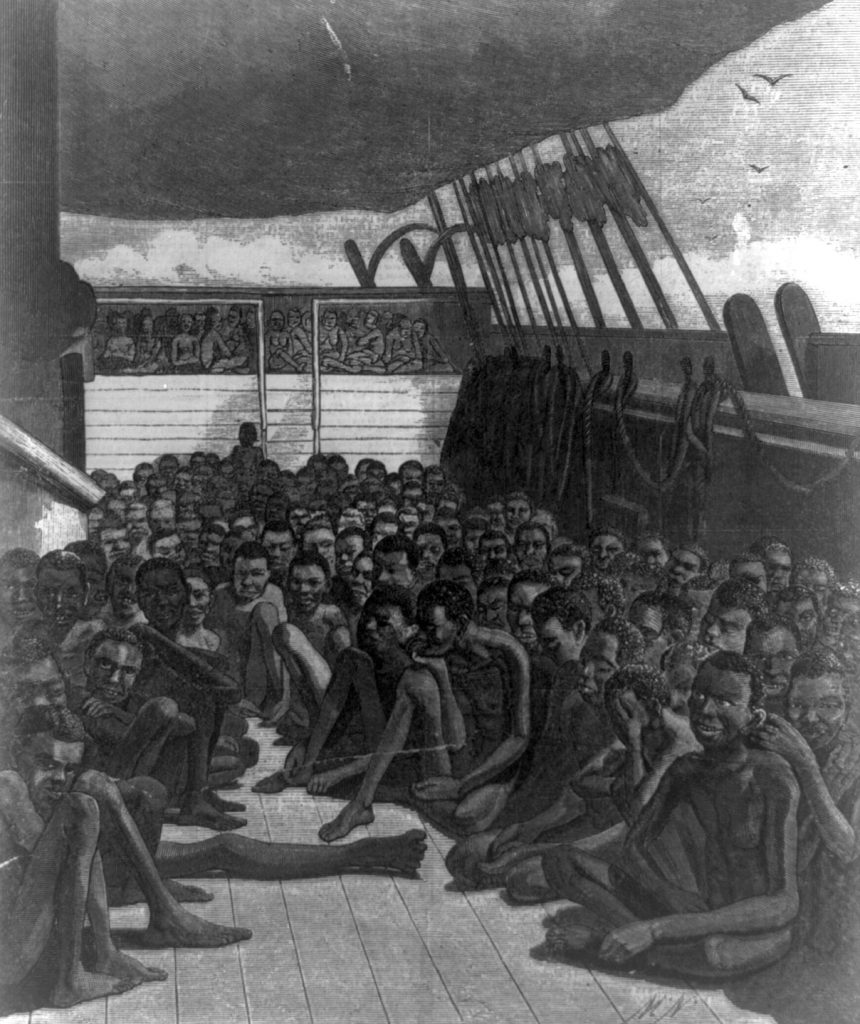

On the first stage of the triangle, ships left from British ports, bound for the west coast of Africa, loaded with goods such as copper and brass bars, textiles and iron wares. This was used as currency in exchange for captured Africans. The second leg of the journey – the ‘Middle Passage’ – transported the captured Africans across the Atlantic to the colonies in the Caribbean and the Americas. This leg is vividly remembered due to horrific-first hand accounts.

Olaudah Equiano’s (c.1745-1797) Interesting Narrative, first published in 1789, detailed the terrible conditions upon one British slaving ship. Equiano was captured, aged eleven, in 1757 in a region of modern Nigeria and transported by slave ships to the British colonies of Barbados and Virginia. Ultimately, Equiano was taken to London by a British naval officer. There he was given the name Gustavas Vassa, and served in the Royal Navy.

After Equiano was set free, he became a prominent abolitionist in Britain. His Narrative was the first account of slavery from the perspective of a captured African. Although the accuracy of its details has been questioned, the narrative reveals something of the true horror of this journey:

“When the ship had got in all her cargo, they made ready and we were all put under her deck … The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air, but now that the whole ships cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us … the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died … This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling [chafing] of the chains and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable”3.

This account of the Middle Passage was much used by abolitionists prior to the abolition of the slave trade by the British Parliament in 1807. It gives an indication of why around eleven per cent of all Africans loaded onto slave ships died in transit. Captured slaves who survived eventually landed in the plantations of the West Indies and North America. There they faced near certain death or a severely shortened lifespan by way of intensive forced labour, supported by a harsh punishment regime.

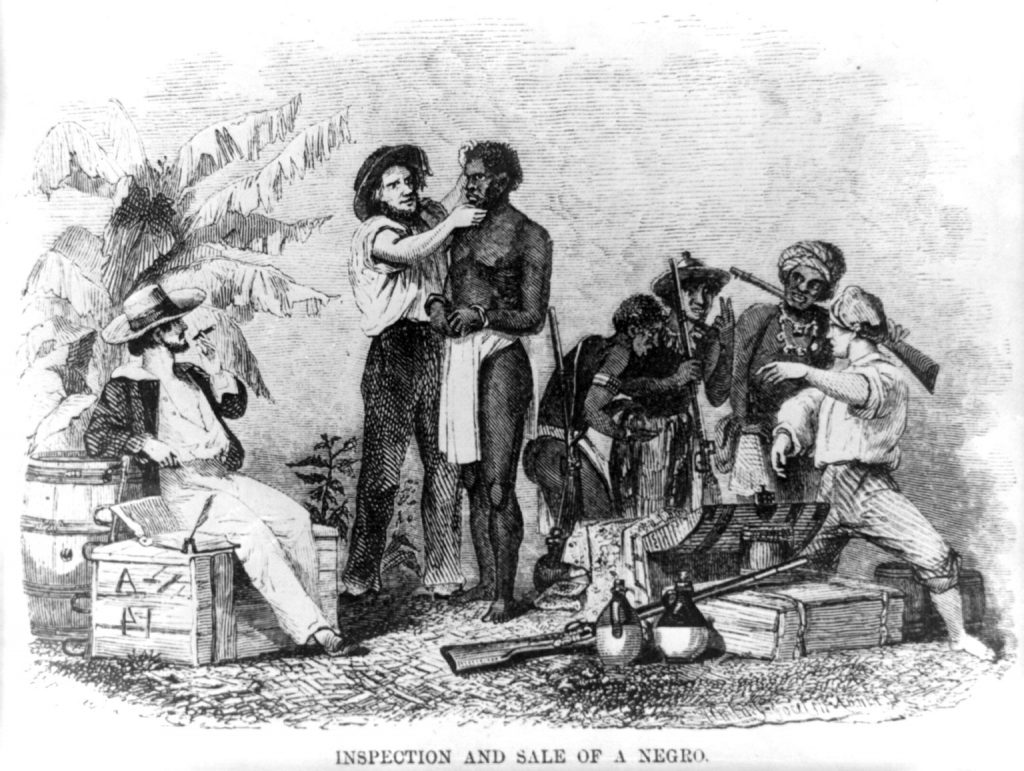

Transported slaves were traded with the colonial planter class for the produce, such as tobacco and sugar, that fellow Africans were being worked to death to grow. The slave ships then took the last leg home to Britain, to realise a profit from sugar, tobacco and rum – then widely promoted as luxurious and desirable products to improve the wellbeing of man.

The form of slavery that the captured Africans were subjected to varied from one colony to another. At its worst, it represented a new means of working people to death, contrasting sharply with more relaxed forms in ancient times and differing entirely from the indentured servitude that had provided labour in the early history of the colonies. ‘Chattel slavery’4, another British concept, was established in the sugar island of Barbados in 1661.

Although slavery had been practised in Barbados since 1636, the Barbadian Code of 1661 was the first legal basis for the system that became prevalent across much of the Caribbean. The master had absolute control and ownership of slaves, who were treated as property or mere chattels. Slaves had no human or legal rights.

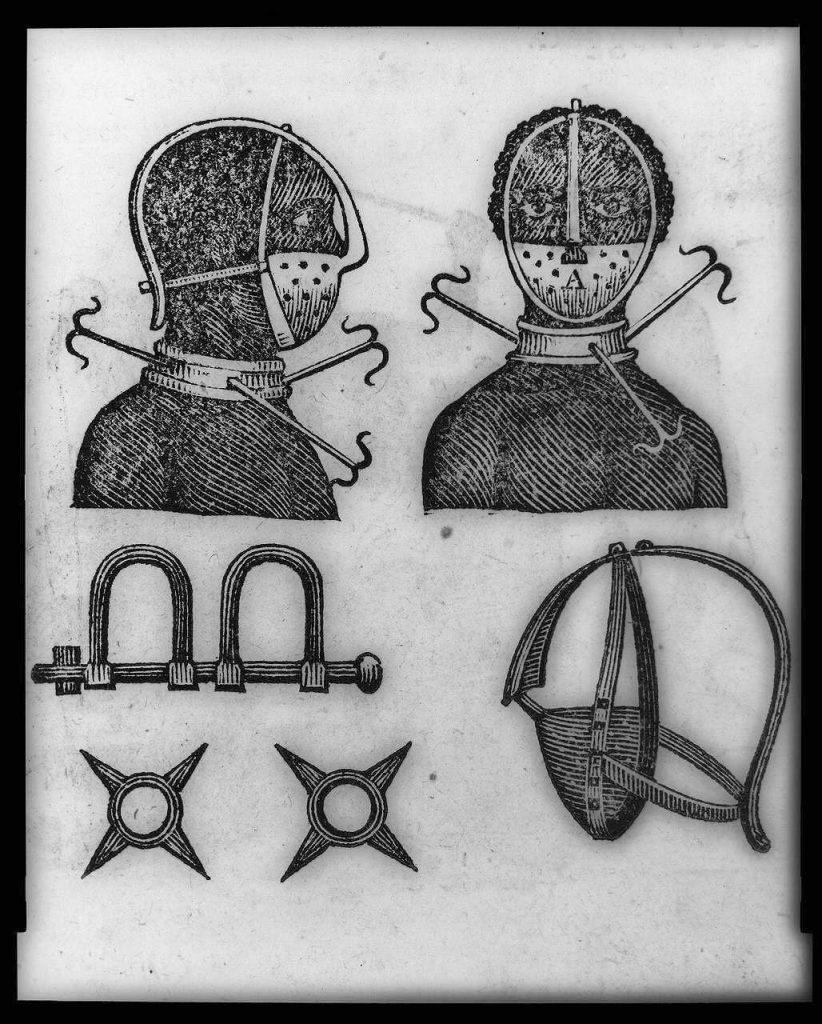

Laws were passed to legitimise almost all actions of the slave owner. The sexual assault of female slaves was legal. So was murder as a means of punishment, although a token fine had to be paid. There were various actions deemed ‘crimes’ that legally justified a slave being punished by the ultimate penalty, including devising plots to escape, starting fires that damaged crops and teaching fellow slaves how to read and write.

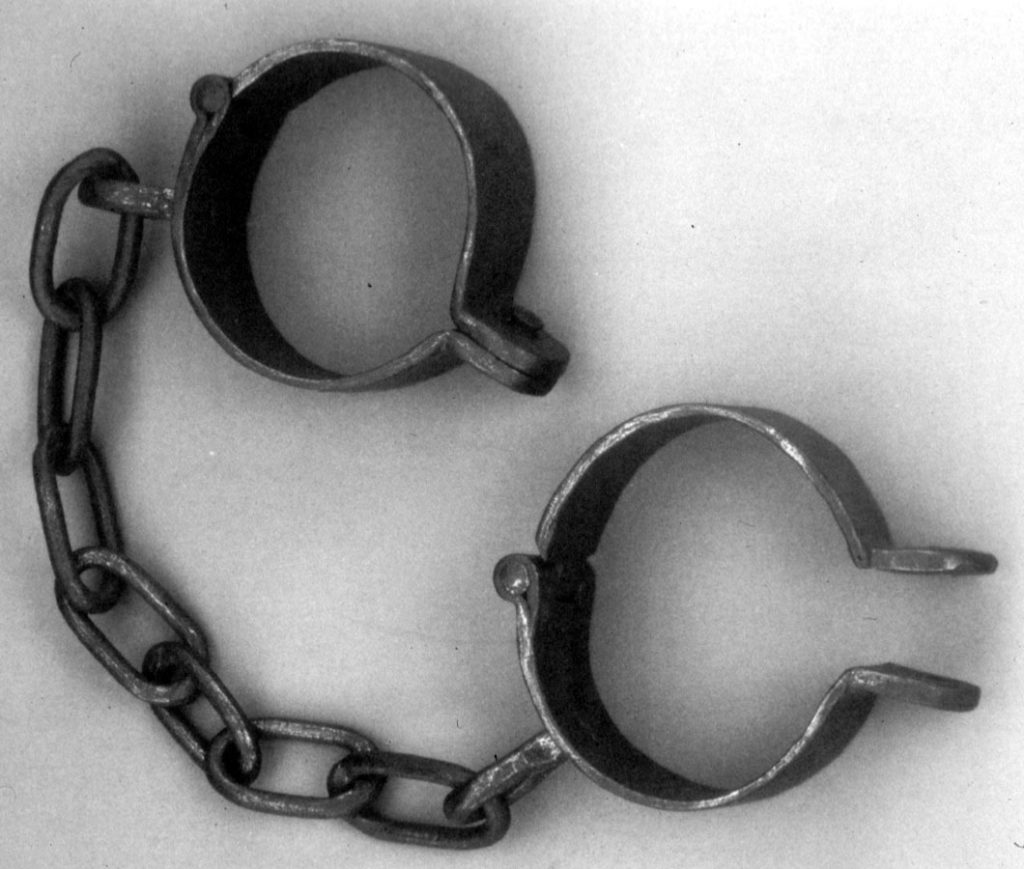

The methods used to control slaves could be brutal: many were shackled in chains and some were sentenced to death by being hung, or even more brutally, burned alive. In contrast, a slave could retaliate only if defending the life of the master. This system was reproduced across generations, perpetuating the cycle of discipline, summary punishment and death.

The demand for slaves in the British colonies developed rapidly in the early years of the eighteenth century. The plantations in the Chesapeake and the Caribbean required increasing numbers of captured Africans as the extent of indentured servitude declined.

The clearest indication of Scottish merchants’ enthusiasm for the slave trade is illustrated by a series of petitions from Dundee, Inverness, Aberdeen, Montrose, Edinburgh and Glasgow sent to Parliament between 1709 and 1711. All protested that a proposed monopoly by the English Royal African Company was contrary to the Union, which guaranteed freedom of trade for British vessels. In 1712, a further economic opportunity emerged when Great Britain acquired the ‘Assiento’, the dubious privilege of supplying slaves to the Spanish colonies.

Appearances can be deceptive. The actual involvement of Scots in the trade did not match the enthusiasm of the petitioners of 1709-11 and did not mirror the increased demand for slaves. It should be noted that the sources and records are incomplete. The Custom Accounts for the Scottish ports survive only for the period 1742-1830. However the general lack of direct Scottish involvement is supported by other circumstantial evidence.

The first recorded slave voyage from Scotland did not occur until 1717. In all, there were twenty-seven recorded slave voyages that left Scottish ports, a further four were funded from Scotland. The majority of them, nineteen, left from Glasgow’s satellite ports, Greenock and Port Glasgow. The number of slaves transported on these Scottish slave voyages from West Africa was between 4,000 and 5,000, with Glasgow ships carrying some 3,000 of the total. The 1760s was the most prolific period of slave traffic and 1766 is likely to have marked the last slaving voyage from Scotland.

This level of involvement – thirty-one voyages over a forty-nine year period – is small when compared with prominent slave ports in England, where the trade was much greater and lasted longer. At its peak, between 1790 and 1799, Liverpool cleared 1,011 slave voyages. The total number of slaves carried by British ships from Africa in the period 1710-69 was around 1.5 million.

Whilst the figures for direct involvement from Glasgow and Scotland as a whole are very low, there are a number of complicating issues. Exact quantification is impossible. One reason is that it was common for Scottish vessels to go to West Africa via European ports such as Rotterdam to load trade goods. As a result, the subsequent destination and purpose of the journey was not recorded in the customs records.

Another problematic feature of the traffic lay in the colonies. There was significant trade in slaves by merchants amongst plantations. Its extent is unknown although individual cases involving Scots can be traced. Neil Jamieson, the trading agent in the Americas of the well-known tobacco lord John Glassford, was involved in the slave trade in the Carolinas.

The existing records provide some detail on the slave voyages from the Clyde. This allows an account of the human story that numbers alone cannot convey. The first slave voyage from Scotland came in 1717, when the George Galley cleared Port Glasgow. It was followed by the Loyalty in 1718 and its sister ship, Hannover, in 1720. All three sailed for West Africa and then to the West Indies and Virginia. Specific circumstances on these last two voyages prohibited further involvement until 1730 when Neptune left Port Glasgow.

The slaving ventures of the Loyalty and the Hannover can be examined in more detail. Both were recorded for posterity as the voyages were beset by particular misadventures. The Loyalty left Port Glasgow in July 1718 for West Africa by way of Europe. The plan was to take on goods to trade for slaves, as the first stage of a longer ‘Triangular Trade’ mission. After being attacked by pirates off Africa it limped into Greenock in May 1720 after disposing of slaves in Barbados.

Loyalty’s sister ship, the Hannover, which sailed from Port Glasgow on a similar ‘Triangular Trade’ voyage in 1720, was owned by a group of ‘merchants of Glasgow’. They employed a factor based in London, Claude Johnson, to purchase trade goods and hire a surgeon, named Alexander Horsburgh. Horsburgh was given an additional free role as ‘supercargo’, which involved responsibility for trading goods. He took full advantage of his commission.

Many slaves died in the horrific crossing. The venture resulted in failure and losses for the investors. This was due, in part, to Horsburgh, who also personally engaged in the trade in slaves on this journey. Horsburgh was arrested when he returned to Glasgow, facing a prosecution brought by the owners in an attempt to recoup their losses. However he was exonerated in 1725.

From an economic perspective, both these ventures were failures and illustrated that the trade in humans, though potentially lucrative, was also high-risk. Whatever moral view of the slave trade was taken before and after 1807, these two failed voyages had a significant practical impact on the future of transatlantic commerce from Glasgow.

The high risks of the trade discouraged further slave voyages until the 1730s. This, in turn, promoted the development of tobacco as the primary focus of colonial trade. Consequently the tobacco trade expanded on the basis of existing networks that had evolved in the period since 1680.

The trial of the ‘supercargo’ of the Hannover, Alexander Horsburgh, had a long-term influence on the entrepreneurial methods of Scottish and Glasgow merchants. In the period of the tobacco lords, merchants preferred to use their own kinship networks to identify representatives they could trust to conduct business in the colonies, instead of giving a commercial carte blanche to outsiders. The other key feature of the colonial trade was the establishment of a monopoly in agricultural goods and household effects – ranging from ploughs to pots and pans – as the basis of payment for tobacco and sugar.

The influence of Scots in the business of slavery reached far beyond the boundaries of Glasgow. They were involved in the major Atlantic ports of Liverpool, Bristol and especially London, which enjoyed as great a dominance of the British economy in the eighteenth century as it does in the twenty-first.

Scots were involved at all levels in the slave trade – as suppliers, financiers and independent slave traders. Existing trading networks and financial connections between Scotland and England were enhanced.

This link between Glasgow, London and West Africa is well demonstrated by the Oswald family. Richard (1687–1763) and Alexander Oswald (1694–1766) came from Caithness and assumed a prominent position in Glasgow society based on the trade in tobacco, sugar and wine. They traded with Virginia, the West Indies and Madeira.

They built ‘Oswald’s Land’ in Stockwell Street in 1742 and invested in landed estates around Glasgow at Scotstoun in 1751 and Balshagray in 1759. That they had links with the slave trade is beyond doubt. Richard Oswald was described as the foremost authority in Glasgow on the slave trade at Alexander Horsburgh’s trial in 1725.

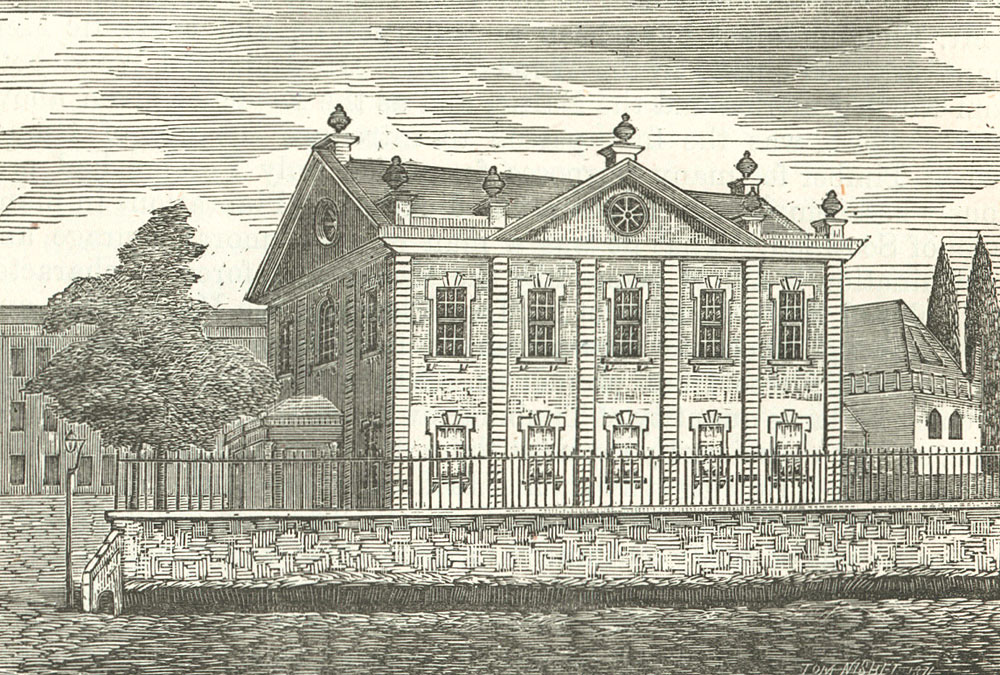

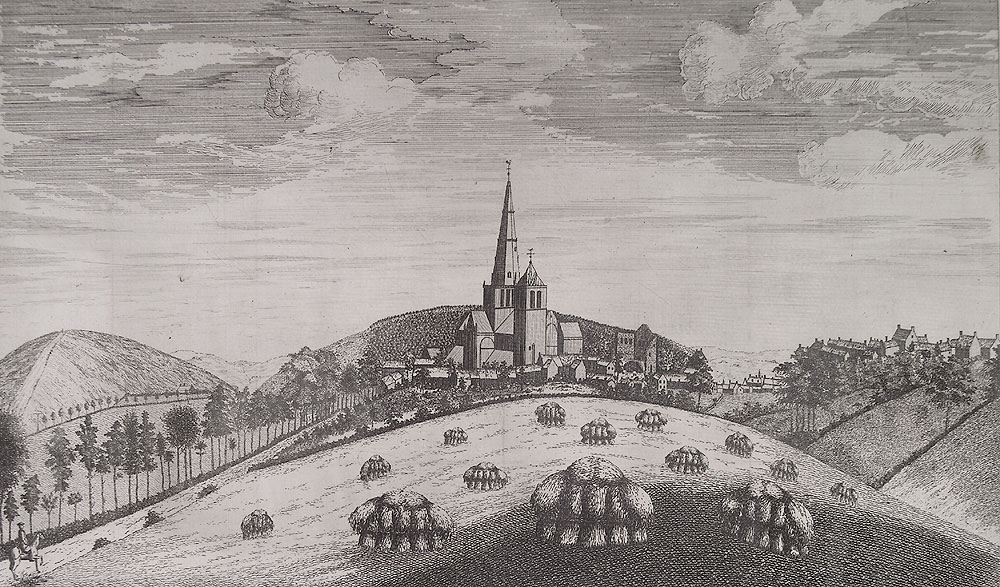

There are many reminders still to be seen in Glasgow’s streets of the Oswald’s standing in the ‘Merchant City’. Richard was commissioned to meet the Jacobite negotiator, Squire Hay, after Charles Stuart, the young Pretender, occupied Glasgow in 1745. The Oswalds were involved in the construction in 1750 of the church of St Andrew’s by the Green, also known as the ‘Whistling Kirk’. Alexander became its first patron. St Andrew’s, similar in style to Glasgow’s Palladian villas, is an enduring reminder of the status of the men who traded in human misery as well as tobacco and sugar.

It was another Oswald, a nephew of the main family, who was to achieve notoriety through his sustained involvement in the slave trade. Richard Oswald (1705-84) relocated to Glasgow in the 1730s to become involved in his cousins’ thriving business interests. He became their colonial representative, responsible for trade in the Caribbean and Virginia, before returning to Glasgow in 1741 as a junior partner in their firm.

Having gained knowledge, contacts and wealth, Richard Oswald moved to London in 1743 to develop his own commercial empire, where he helped set up the firm of Grant, Sargent and Oswald. He branched out into the trade in tobacco and eventually sugar, horses and slaves. Ultimately he purchased four plantations in the Caribbean and over 30,000 acres in East Florida.

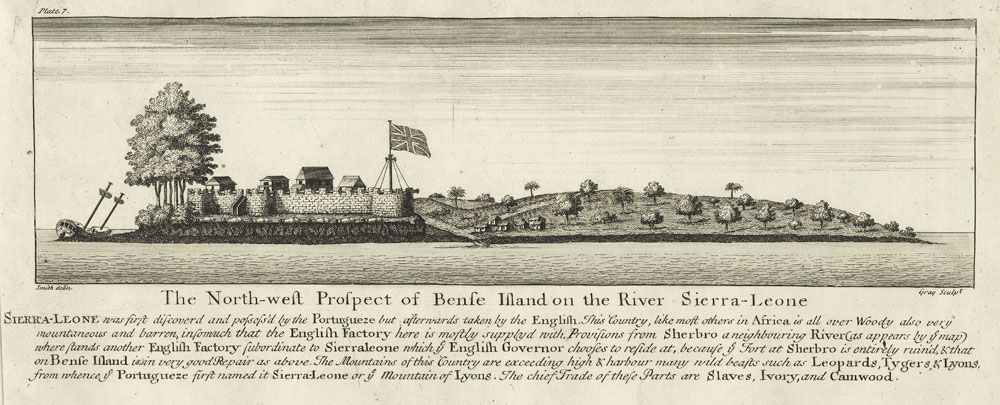

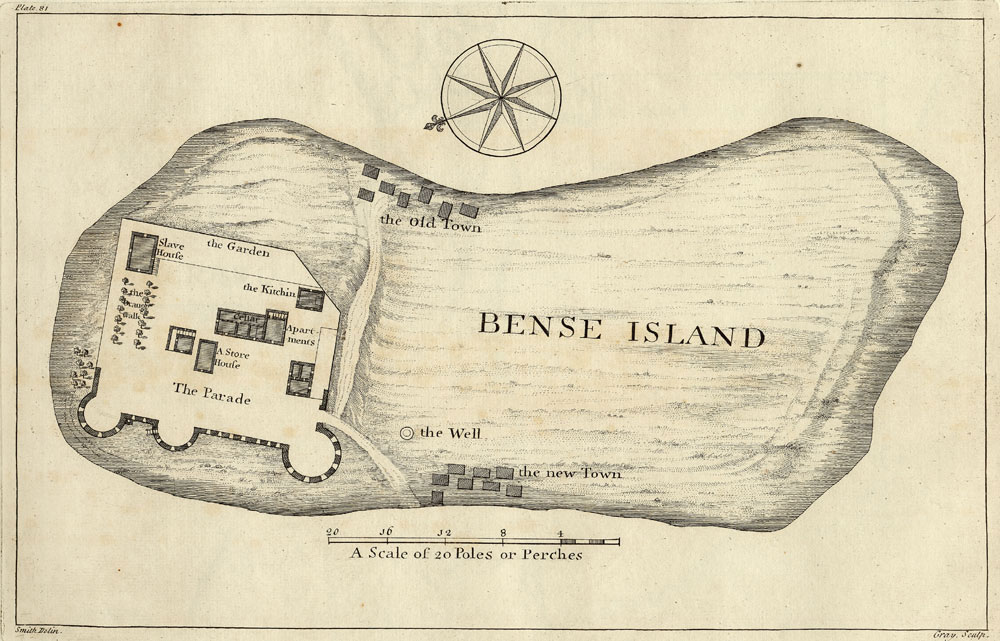

Bance Island, off the coast of Sierra Leone, purchased in 1748 by Richard Oswald and five other London-based Scots, was witness to the very worst practices of the slave trade. The island had been used by the English Royal African Company as a trading fort for slaves since the 1670s but had been abandoned by the 1740s. Oswald and his partners made it the most fortified entrepôt in West Africa.

Bance Island had its own shipyard and fleet, which patrolled the coast of the mainland in search of slaves. As such, it provided a convenient marketplace for merchants from a number of European slaving nations, allowing them to bypass local African slave traders.

Although few slave voyages from Glasgow are recorded – the Agnes transported 226 slaves to Virginia in 1760 – there was a powerful Scottish presence on Bance Island. Between 1751 and 1773 around a quarter of the employees were Scots and some originated from the Glasgow area. Kinship networks and other contacts with overseas merchants such as Oswald helped to introduce young men into a career in the colonies, including the slave trade.

Bance Island mixed the horrific with the bizarre. Oswald constructed a two-hole golf course for the enjoyment of visiting slave traders. Captured Africans were used as caddies, complete with tartan uniforms, which Oswald imported from Bannockburn and Glasgow.

Richard Oswald also ran his own slave voyages, mostly to Charleston, to meet the demand for slaves on the rice plantations of South Carolina. It has been estimated that during Oswald’s period, from 1748 until 1784, around 13,000 captured Africans were transported into chattel slavery in the New World.

Oswald accrued a huge fortune, estimated at £500,000 when he died in 1784, equivalent in modern terms to over £50 million. Before he died, Oswald purchased an estate at Auchincruive in Ayrshire. He also remained influential in high society in London and Glasgow. He was a diplomat at the Treaty of Paris which concluded the American War of Independence in 1783. He had personal friends in high places, including Adam Smith and Benjamin Franklin as well as his American business partner in Charleston, the plantation owner Henry Laurens (1724-92), who became President of the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War.

The slave trade brought the Oswalds status, influence and wealth. When he died, Oswald of Auchincruive was lionised in a Glasgow newspaper:

“Perhaps there are few men, whose loss will be more generally felt, or more sincerely regretted, than that of Mr Oswald, for few had a finer understanding, more liberal sentiments, or more extensive information. Blessed with affluence, his principal study seemed to be to employ it in acts of kindness and generosity”5.

There is a more lasting memorial to the Oswalds in an ironic setting. They were granted a family burial plot in Glasgow Cathedral, which is to be found in the nave under slabs marked ‘G.O.’ – the only merchant family to be buried there. However, Richard Oswald of Auchincruive is buried in St Quivox Parish Church , Ayrshire.

The cathedral also has several memorials to tobacco and sugar merchants, perhaps ironic considering their links with slave labour. There is a stained glass memorial to Alexander Speirs of Elderslie (1714-82), one of the original tobacco lords and sometimes called ‘the mercantile god of Glasgow’.

The ancient high church of Glasgow also features memorials to Sir James Stirling of Keir (1740-1805), who owned plantations and slaves in Jamaica and to Andrew Cochrane (1692-1777), a Virginia Don who owned the King Street Sugarhouse and was six times Lord Provost of the city. The burial plot of the Buchanans, another of the great tobacco families from Glasgow, is located at the cathedral’s entrance. The message from the Glasgow merchants’ spiritual home was clear, overlooking the human cost, it was tobacco that made Glasgow great.

Next section:

References

- Mark Duffill, The Africa Trade from the Ports of Scotland, 1706–66. Slavery & Abolition, 2004 p102.

- Charles William Taussig, Rum, Romance and Rebellion, 1928.

- Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself. Vol. 1, 1789 Page 39.

- M. Asante, The ideological origins of chattel slavery in the British world. Slavery Remembrance Day memorial lecture, 2007.

- The Glasgow Mercury, 14 November 1784.