In the early seventeenth century, Scotland’s economy was still very much like that of a modern-day third-world country: it was largely rural, dependent on the export of foodstuffs, animal produce and primitive manufactures and the import of luxury goods. However by 1750, it was well on its way to becoming one of the most powerful industrial economies in the world.

Much of the capital that primed Scotland’s startling transformation came from across the Atlantic, from the plantations of North America and the Caribbean. Manufacturing towns such as Glasgow expanded rapidly; the profits from the plantations and associated trade supported a complex urban economy and stimulated an agricultural revolution that underpinned Scotland’s growth. Domestic expansion was supported by the entrepreneurial skills of merchants, helping to establish what has recently been termed ‘the Scottish Empire’1. Scotland was built on shrewd investment, venture capital – and the blood and sweat of slaves.

Initially, the Atlantic trade from Scotland developed in spite of its larger neighbour. After Scotland and England were joined by the Union of the Crowns in 1603, a series of Navigation Acts were introduced to protect the trading interests of the rapidly expanding English Empire. These acts effectively classified Scotland’s commerce as that of a ‘foreign nation’.

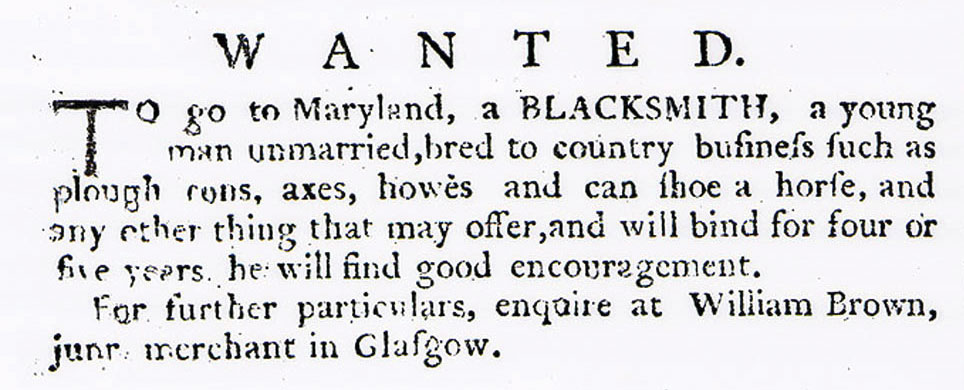

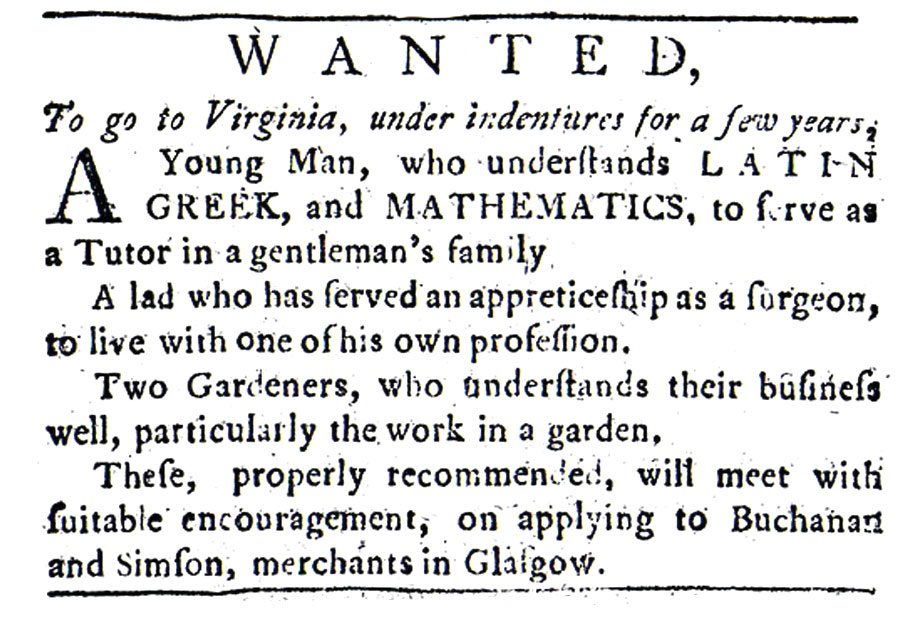

Scots merchants, however, had already established effective trading links with the English colonies and continued to trade covertly, especially in Virgina, New Jersey and the Carolinas. A customs agent for Scotland estimated that at least twenty-four Scottish ships were operating illegally in the 1680s.Vessels from Glasgow transported criminals, indentured servants and political exiles to the New World. A good deal of this traffic was organised by the Scottish Privy Council, turning a blind eye to Westminster legislation.

In the 1670s and 1680s, a time of religious and political strife in Scotland, there was a steady supply of forced emigrants, many of them Covenanters transported to Virginia and Maryland. A contract to carry out these transportations was actually awarded to Glasgow merchants in 1685. It remained in place until the middle of the next decade, when the increasing use of black slave labour made the venture unprofitable. Some of the origins of the tobacco and sugar trades that made Glasgow great can be identified in the Restoration period when the mainstay of Scotland’s exports were enemies of the state and criminals.

Glasgow was ideally situated to take advantage of the rapidly expanding transatlantic trade and rapidly developed from a modest market town with a large hinterland to a burgeoning centre of international commerce. Direct trade, recorded as early as 1656, in addition to existing links with Ulster and Europe, transformed the economy.

By 1671, according to burgh tax rolls, Glasgow was Scotland’s second largest burgh behind only Edinburgh. This was due in no small part to colonial trade. One explanation for the change is psychological: ‘a spirit of commerce appears to have been raised among the inhabitants of Glasgow’2. Whatever the truth of this, a clear indication of the shift in commercial focus towards the New World was the construction of four sugar processing houses between 1667 and 1700, making sugar boiling one the mainstays of Glasgow’s new and fast-growing economy. They were the first buildings in Glasgow devoted to colonial trade.

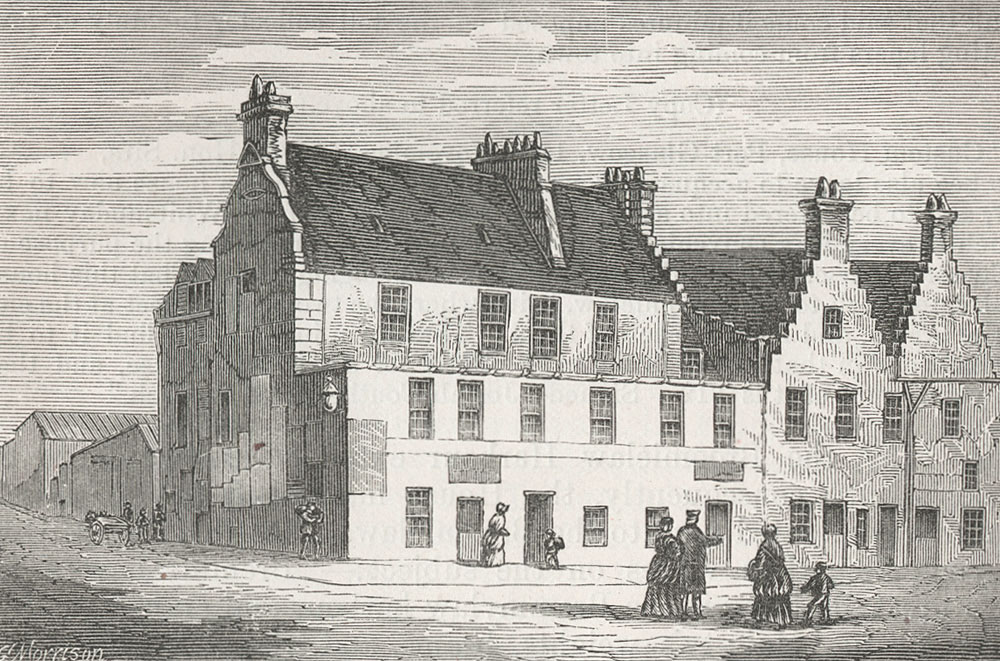

All four sugar refineries were financially supported by merchant families who already had a foothold in the trade from Barbados and Jamaica. The Wester House was built for the merchant Peter Gemmill in 1667 followed by the Easter House, later called the ‘Old Sugar House’, in 1669. By 1680, both factories were distilling rum from molasses, a by-product of sugar refining.

The Easter House, a five-storey, crow-stepped gabled building at 139 Gallowgate was later owned by Robert McNair (1703-79) and his wife, Jean Holmes (b.1703), prominent eighteenth-century Glasgow shopkeepers. Amongst their wares were expensive sugar products such as candies, syrup and treacle. The sugar trade produced some of the first industrial fortunes in Glasgow.

Increasing demand for foreign luxury items promoted the development of Glasgow as a centre of maritime commerce. The city’s merchants had previously made use of ports in the Firth of Clyde at Irvine, Dumbarton and especially Ayr, as the Clyde was too shallow for large vessels. Goods from the plantations were transported up the river in small gabbart boats. The underdevelopment of the Clyde hindered progress:

“The situation of this towne in a plentifull land, and the mercantile genius of the people, are strong signs of her increase and groweth, were she not checqued and kept under by the shallowness of her River, every day more and more increasing and filling up”3.

This situation was rectified in two ways. A harbour at the Broomielaw was built in order to land goods beside nearby warehouses. But a more ambitious project was the construction of a port further down the Clyde.

In 1667 the burgh council purchased land at the estate of Newark, in the burgh of Dumbarton. There it financed the construction of a large deepwater harbour, warehouses, a customs office and a small town on the southern bank of the upper Clyde – Port Glasgow, soon to be dubbed the ‘Piraeus of Glasgow’4. It gave Glasgow its first direct entrepôt for larger ocean-going vessels and their trade goods. After 1680 Port Glasgow rapidly became one of the busiest ports in Great Britain, eclipsing trade through Ayr. By 1681, at least five Glasgow ships a year were crossing the Atlantic to destinations in New England and the West Indies.

Glasgow’s increasing share of the colonial trade came at a time when the workforce in the tobacco and sugar plantations of the New World was changing. Indentured servitude, largely dependent on the forced transportation of emigrants, remained prevalent until the mid-1690s but the use of black slave labour was rising dramatically. The trend was first seen in Barbados and Jamaica, where plantation owners were using only black slave labour by the 1680s. By 1710 the planters in the Chesapeake region of America had followed suit.

After a series of failed attempts to establish Scots colonies in South Carolina and New Jersey, a hugely ambitious project was initiated in the mid-1690s. The Darien scheme was a response to a period of acute economic crisis which afflicted Scotland. The 1690s became known as ‘the seven ill years’5 due to repeated harvest failures, grain shortages and starvation. Mortality rates soared. Perhaps as many as 160,000 Scots died from famine and emigration, and fertility rates plummeted. The strategy of direct trade with the New World was seen as a universal cure for Scotland’s economic failings.

The legal foundation for the Darien Scheme rested on two Acts of the Scottish Parliament. The ‘Act for Encouraging of Forraigne Trade’ in June 1693 was followed in June 1695 by a further Act which established ‘The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies’. The Company was granted extensive privileges; a twenty-one year monopoly on the trade between Scotland and America, during which it was exempt from customs duties and a perpetual monopoly on the trade with Asia and Africa. It was also authorised to purchase, equip and arm ships.

Several factors influenced the forming of the Company of Scotland. It evolved as the result of a campaign by influential London-based Scots such as William Paterson to challenge the monopoly of the East India Company. Only after the English Parliament blocked its efforts to raise English merchant capital as well as Scots did the scheme become something of a patriotic crusade.

The required £400,000 of venture capital for the Company was raised by the summer of 1696. This was around a quarter of Scotland’s liquid capital – a massive investment, with Scotland’s landed elite prominent amongst the subscribers. Not surprisingly, Edinburgh and Glasgow contributed 30 per cent of the total. Glasgow Town Council put £3,450 into the scheme whilst private investors in the burgh invested £13,800. Yet this was less than might have been expected from the city’s merchants. The only significant capital from the burgeoning colonial industries was the £3,000 invested by the proprietors of the Easter Sugar works.

The project seemed simple yet ingenious. A Scots trading enterprise transporting goods across the sixty-mile Isthmus of Darien in Panama between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans would have revolutionised trade between Europe and the New World. Freight times and costs would have been drastically reduced. This was, in effect, a predecessor to the modern Panama Canal.

The first expedition left the Port of Leith in July 1698 bound for Panama. 1,200 settlers – described as the ‘elite of Scottish manhood’ – established New Edinburgh on the Isthmus. Fort St Andrew was constructed to protect the fledgling township. The settlement failed due to a combination of poor planning, a lack of provisions, the unforgiving terrain and disease. Many settlers died and only one of the four ships in the expedition returned.

A second expedition left Leith in June 1699, before the fate of the first was known. It found a ruined and deserted site at New Caledonia and was confronted by Spanish forces which attacked the fledgling colony and forced the settlers to leave. A third mission, which initially promised to make a profit, was abandoned in April 1700. In all, thirteen ships were commissioned to cross the Atlantic but only three returned. Over 2,000 lives were lost. This remarkable Scottish attempt at establishing a trading empire was a tragic failure.

Financially, the Darien Scheme almost bankrupted the country. It added economic grievances to a growing constitutional conflict between the English and Scottish parliaments. But it also, in retrospect, marked a turning-point in Scotland’s role in colonial trade. Instead of trying to found Scottish colonies in the New World, Scots increasingly tapped into the network of English colonies across the West Indies and along the American seaboard from Charleston to New York. Despite its failure, the collapse of the Company of Scotland and the Darien scheme reinforced a belief that Scotland’s commercial future lay in the New World, where slavery was widely held to be a sure and valid means of making huge profits.

The Darien scheme also marked the first attempts by Scottish merchants to involve themselves in West African slavery. An investigation into the viability of the Company trading in slaves from West Africa was mooted as early as 1696. In 1699 the African Merchant went to the Gold Coast to look into a plan to build a Scottish trading post with a military fort for protection as a base for trading in slaves, gold and ivory.

Nothing seems to have come of the 1699 voyage but two other attempts followed. In 1700, in a last attempt to make the Darien venture profitable, the Duke of Hamilton supported an ambitious scheme to establish a slave trading site at the French settlement of Cape Bonne Esperance (the Cape of Good Hope). Captured West Africans were to be transported to Panama to supply labour for its gold mines but the collapse of the Darien scheme overtook these plans.

The African Merchant, the only profitable venture by the Company, returned to Leith from West Africa with only trade goods but the Company also licensed slaving voyages. On their return voyage from Darien in 1701, the Speedy Return and Content stopped at Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, intending to trade in spices, gold dust and ivory. Instead, slaves were purchased from pirates and sold on the nearby French colony of Reunion Island. It was an isolated episode which smacked of opportunism rather than strategy but it did herald future developments.

The Act of Union of 1707 laid the foundations for Scotland’s large-scale involvement in the colonial trade across the Atlantic. It is significant that of the twenty-five Articles of Union prepared in 1706, fifteen were economic in nature. Article IV allowed:

“Full Freedom and Intercourse of Trade and Navigation to and from any port or place within the said United Kingdom and the Dominions and Plantations thereunto belonging”.

This Article opened up established trade routes for Scottish merchants, including the slave trade from Africa.

A dazzling array of new commercial activities materialised in what would become the largest empire in history. Scots gained access to the English colonies of Virginia, Maryland, East New Jersey, South Carolina, Pennsylvania and New York; opportunities in the Caribbean plantation colonies of Jamaica, Barbados and the Leeward Islands and footholds on the west coast of Africa in modern Gambia and the Gold Coast, now Ghana.

In the seventeenth century, this growing collection of territories was known as the ‘English Empire’. It is no coincidence that it was in 1708, a year after the Union of Parliaments, that it was rechristened the ‘British Empire’6. Union brought a further, enormous benefit. The Darien expeditions had been vulnerable to attacks by Spanish men-of-war and pirates. Article V of the Act of Union classified all Scottish and English shipping as ‘British’. Scottish traders as a result came under the protection of the formidable Royal Navy.

Union provoked a range of contradictory emotions and rival interests in Scottish society. The great Scots patriot, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, termed the prospect of free trade as ‘the bait that covers the hook’. Yet there was widespread popular opposition across Scotland in 1706-7, particularly in Glasgow, where there were riots and vociferous denunciations of Union from the pulpit.

Many merchants, in Glasgow and elsewhere, robustly opposed Union, sharing Saltoun’s fear that it would be the ‘best handle ever… for oppression and slavery’7. Instead, it underpinned much of the future economic development of Scotland by providing access to new markets across the globe, under the protectorate of the most powerful navy in the world. In the process, ironically, it established many influential Scots as advocates of slavery and profiteers. And nowhere was this more so than in Glasgow’s Merchant City.

Next section:

References

- T.M. Devine, Scotland’s Empire 1680-1815, 2004.

- James Gibson quoted in T.C. Smout, The Development & Enterprise of Glasgow, 1556-1707, 1960 Page 201.

- J. D. Marwick (Ed.) Miscellany of the Scottish Burgh Record Society, 1881 p26.

- Robert Renwick, John Lindsay, George Eyre-Todd, History of Glasgow, 1931 p335.

- Michael Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 2004 p307.

- John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Containing the History of the Discovery, Settlement, Progress and Present State of All the British Colonies, on the Continent and Islands of America, 1708.

- Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun quoted in C.A. Whatley, The Scots and the Union, 2006 p297.