After the American War of Independence, the tobacco trade declined to such an extent that Glasgow’s ‘Golden Age of Tobacco’ was over. However, other opportunities in the New World arose as the rapid expansion of a second British Empire became a significant factor, seen first in increasing Scots involvement in the West Indies.

By 1815 and victory over France, British predominance had been established in the Caribbean: Grenada, St Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago were added to earlier colonies such as Barbados and Jamaica. The British Empire increased in both size and population, offering a variety of new opportunities. This process created monopolies in items such as textiles and fish and stimulated the existing export trade from Scotland. The sugar industry expanded and by 1790 the colonies in the West Indies became Glasgow’s primary trading outpost.

The economic opportunities in the sugar islands were a ‘pull factor’ for many young Scots, disenchanted with adverse conditions at home. There was a long tradition of emigration to the Caribbean, often as a temporary measure. Emigrants were typically young men in their early twenties, such as the young Robert Burns who considered taking up a post of plantation book-keeper in Jamaica before the Kilmarnock Edition of his poetry became commercially successful.

It has been estimated that between 12,000 and 20,000 Scots emigrated to the Caribbean in the period 1750 to 1800. They went to the Windward Islands of Dominica, St Vincent, Tobago and Grenada but the key destinations were Antigua and Jamaica. In 1774, a third of the white population of Jamaica were Scots or of Scottish descent. In 1765 around a quarter of the purchasers of land in St Vincent and Dominica gave their home residence as Glasgow.

It has been argued that a specific mentality made the Scots ideal for administration of the slave economy and they adopted a unique role. Scots became involved at all levels, including the financing and over-seeing of plantations and as merchants, lawyers, tradesmen and doctors.

As a proportion of the total the Scots were over-represented in the colonial ruling elite and Glasgow merchants became prominent plantation owners in the sugar colonies. The Stirling family of Keir and Cawder owned estates near Glasgow and bought plantations in Jamaica in the mid-eighteenth century.

The head of the family, James Stirling, had twenty-two children. Many emigrated to the Caribbean as merchants. One of his sons, Archibald Stirling, developed the plantations and employed relatives as planters on their estates in Jamaica. Ultimately the ‘Frontier’ and ‘Hampden’ estates proved non-viable, despite an increase in the use of slave labour to boost productivity. However the family’s connection with Jamaican plantations and slavery lasted until around 1850.

There were several West India merchants and companies based in Glasgow owning Caribbean plantations in the period 1760-1815. John McCall and Sons owned the Westmoreland, Union and Mount Arran Estates in Trinidad. R. Dunmore and Co. had ownership of the Large Estate, whilst Robert MacKay and Co. ran the Heywood Hall Estate, both in Jamaica.

Bogle, Scott and Co. owned the Mountraven Plantation in Grenada. John Campbell and Sons had several plantations in Grenada and British Guyana. There were significant vested interests in Glasgow in the West Indies sugar industry which sought to protect and expand both it and the chattel economics on which it rested.

The sugar trade depended on the expansion of the plantation system which, in turn, demanded greater use of chattel slave labour. By 1750 almost 90 per cent of the British West Indies population were black slaves. The slave experience was horrific on a variety of levels.

Slave labour was primarily used for land preparation, harvesting and the boiling of sugar canes. The working day lasted from dawn till dusk; it involved the majority of the black population. Only very young children and the elderly were excused. The labour was extremely intensive, especially during harvest time, and many slaves were literally worked to death.

The labour needed to make the sugar trade viable was considerable: it took around twenty tons of sugar cane to produce one ton of export sugar. Slave mortality was high: the average working life was less than five years, whilst between 25 and 50 per cent died within three years of arriving in the plantations. Harsh treatment was exacerbated by a poor diet, malnutrition and a severe punishment system. Reproduction and fertility rates were low. Together, these factors served only to generate a greater demand for more black slaves from West Africa.

The methods used to control slaves were brutal and oppressive, including death by hanging and being burned alive for escaping. For lesser crimes, slaves would be shackled in iron chains. Mary Prince, who was born into slavery on the British colony of Bermuda, described the punishment of slaves in 1831:

“Mr. D. was usually quite calm. He would stand by and give orders for a slave to be cruelly whipped, and assist in the punishment, without moving a muscle of his face; walking about and taking snuff with the greatest composure. Nothing could touch his hard heart–neither sighs, nor tears, nor prayers, nor streaming blood; he was deaf to our cries, and careless of our sufferings. Mr. D. has often stripped me naked, hung me up by the wrists, and beat me with the cow-skin, with his own hand, till my body was raw with gashes. Yet there was nothing very remarkable in this; for it might serve as a sample of the common usage of the slaves on that horrible island”1.

This cruel regime was maintained and slave codes refined in order to maximise exports of sugar – and profits. The sugar islands were integral to the British economy. The accumulated wealth of the colonies was valued at £30 million in 1800. Scotland increasingly developed an economic dependence on sugar; the trade from the West Indies in 1790 represented around a quarter of the nation’s total imports and a quarter of total exports. Despite the prominence given in Glasgow’s history to the ‘tobacco lords’, the sugar trade, established in Glasgow since 1670, remained an important industry long after the collapse of its tobacco trade.

A number of mercantile companies in Glasgow made vast fortunes through an almost complete monopoly on sugar imports into Scotland in the period after 1783. One of the most prominent in the ‘sugar aristocracy’ was the large firm of Alexander Houston and Co. The company had its origins in a partnership of two Scots visitors to the Caribbean island of St Kitts in the early eighteenth century.

On their return to Glasgow in 1732, Major James Milliken and Captain William McDowall purchased a sugar house. The arriviste McDowall further flaunted his colonial gains by acquiring the Shawfield Mansion in 1727. The partnership developed further when Milliken and McDowall joined up with Alexander Houston of Jordanhill to form The Ship Bank, Glasgow’s first financial institution.

By importing sugar and cotton into Glasgow from Jamaica and the Windward Islands and exporting commodities such as ‘slave cloth’ to the plantation owners, Alexander Houston and Co. made profits at both ends of the trade. The firm had seven plantations in Grenada, maintained by close associates. By 1796 these realised a profit of £411,000, around £31 million today. It tried to adopt the store system, first adopted by the tobacco lords, by extending credit to overseas plantations and in the process developed huge debts. The company went bankrupt in 1800, as a result of the ‘immense speculation’ of Alexander Houston in purchasing slaves ‘the worst financial disaster in the history of the British slave trade’2.

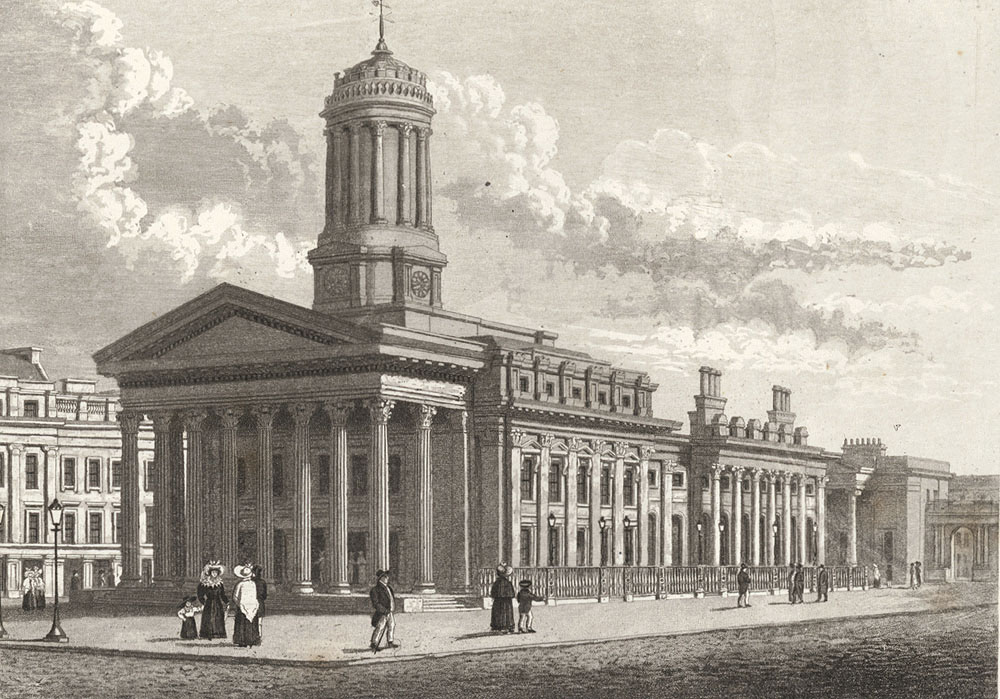

The building which is now Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art has a long connection with slave plantation economics. The Cunninghame Mansion, now the core of the building in Royal Exchange Square, was built in 1778 for William Cunninghame of Lainshaw (d.1789), one of Glasgow’s most prominent eighteenth-century merchants.

Cunninghame had significant interests in both the Virginia tobacco trade and the West Indies sugar trade. He owned the Grandvale plantation in Westmoreland, Jamaica, which had 300 slaves.Cunninghame purchased three plots in what is now Queen Street but which was then Back Cow Lone, a country track. He spent £10,000, a huge sum worth around £1 million in today’s terms, on his townhouse in an attempt to outdo the nearby Shawfield and Virginia mansions.

Cunninghame’s mansion had distinctive Palladian features, including classical pilasters and pediments above the windows on the front of the building with the Cunninghame crest. Described as ‘one of the most splendid houses in the west of Scotland’, it stood in stark contrast to the semi-rural conditions that still prevailed over much of what is now the centre of modern Glasgow. Cunninghame had the Latin motto ‘emergo’ – ‘I emerge’ – etched on his mansion, a boast of his own rapid rise in society and a testament to the position of Glasgow as a global economic powerhouse. The mansion took on a new lease of life as the Royal Exchange in 1829 but its economic connection with chattel slavery remained.

The urban shift westwards of the commercial class in the nineteenth century was reflected in the construction of several prominent buildings in the area around what is now George Square. The Tontine Tavern, previously the social and commercial headquarters of Glasgow, was no longer frequented by the tobacco lords. The Royal Exchange was proposed to provide a new centre in 1827. A committee was formed and the huge sum of £60,000 was raised by subscription.

The Cunninghame Mansion was purchased and transformed into the Royal Exchange by David Hamilton (1768-1843) sometimes known as the father of Glasgow’s architecture. It fast became the centre of Glasgow’s commercial life. James Ewing of Strathleven (1775-1853) took a leading role in its creation as head of the committee and the largest single contributor.

Ewing was highly prominent in Glasgow civic life; an LL.D. of Glasgow University in 1826, Lord Provost in 1831 and elected M.P. for the city in 1832 after the Reform Bill. He also inherited a number of West Indian interests from his father, and had worked as an agent for the imports from the colonies. He made a variety of philanthropic contributions to Glasgow society, including bursaries to Glasgow University.

The shift in focus from Virginia to the West Indies was reflected in the transfer of civic influence to sugar traders, although many came from tobacco dynasties. West India merchants controlled the Town Council in the 1790s and monopolised the office of Lord Provost between 1800 and 1815.The sugar aristocracy, however, never enjoyed the unrivalled authority formerly exercised by the tobacco lords as they had to contend with diverse and growing interests of the Chamber of Commerce, the Merchants House and the Trades House.

The Merchants House followed the commercial exodus west, moving its headquarters in 1874 to the present location in West George Street built to designs by John Burnet. Some older merchant traditions were respected and retained. It was agreed in 1817 that the Merchant’s Steeple, near the Trongate, was to remain, which it does to this day. The copper sailing ship, atop a globe, which adorns the top storey of the building, is a replica of the original on the old Merchant’s House. Its motto, engraved in stone –‘toties redeuntes eodem’ (‘So often returning to the same place’) – is further testament to the city’s dependence on trade with the New World. The Merchants House strictly forbade involvement in the slave trade. It set ‘Scripture Rules for buying and selling’ which prohibited its members trading humans as slaves3. Yet the same merchants made vast fortunes from industries wholly dependent on chattel slavery.

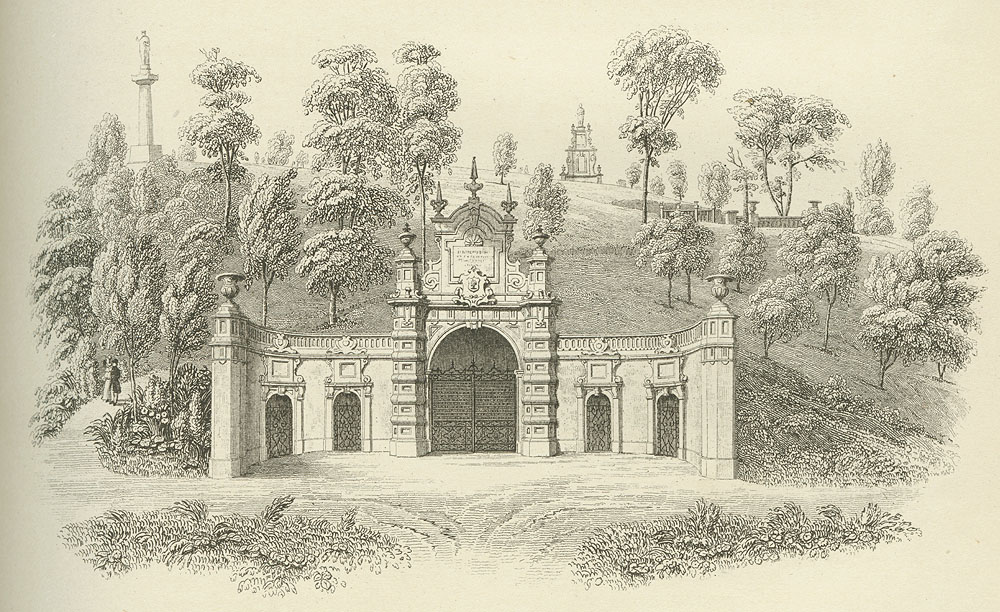

James Ewing was a case in point. In addition to political office, he was Chairman of the Chamber of Commerce in 1818-19 and Dean of Guild of the Merchant’s House in 1816-17 and 1831-32. His lasting legacy, however, was as the leading influence for the development of the Glasgow Necropolis, modelled on Pėre Lachaise in Paris. The Necropolis is acclaimed as one of the true marvels of historic Glasgow.

Ewing proposed plans to the Merchants House in 1828 for a cemetery near the Cathedral for ‘the citizens and merchants families of Glasgow’4. The layout was drawn up by David Hamilton and John Baird, whilst the architect for the monumental entrance façade was John Bryce. It was as Lord Provost that Ewing laid the foundation stone in 1834.

James Ewing one of the most influential of Glasgow’s citizens, was at the same time, a slave plantation owner. A contemporary account denounced him as a major player in slave economics:

“We have reason to believe that he is either the absolute proprietor of numerous ‘gangs’ (as they are called) of Slaves in the Colonies, or what is pretty near the same thing – that he has advanced money to West Indian Planters, taking as security for it a mortgage, or right, not only to the estates of the planters, but to the slave population existing upon them”5.

Ewing’s involvement in slavery attracted criticism during his lifetime. Yet even his critics acknowledged his role as a philanthropist – he bequeathed large sums across the city, including £10,000 each to the Royal Infirmary and ‘decayed Merchants’ – whose fortune came from plantation economics. He died in 1853, leaving £280,000, about £24 million in modern terms6.

James Ewing’s granite sarcophagus in the Necropolis was sculpted by John Mossman, the pre-eminent Glasgow sculptor of his age. In time, the Necropolis became the most fashionable place to be buried in the burgeoning Victorian city. Many merchants are buried there.

In contrast to the memorials in the Necropolis funded by plantation economics, Glasgow’s staunch opposition to slavery is illustrated by the memorial to the Rev. Ralph Wardlaw (1779-1853) one of the leading emancipationists in Britain after 1833. Ironically, Wardlaw was James Ewing’s first cousin. This family paradox was mirrored in Glasgow as a whole. During this period the city had an economic dependence on slavery, yet at the same time it spawned a movement dedicated to its abolition.

Next section:

References

- Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince related by herself, 1831.

- Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade, 1997 p538.

- Susan Milligan, The Merchants House of Glasgow 1605-2005, 2005 p20.

- Nigel Willis, James Ewing of Strathleven nd.

- The Reformers Gazette, 6 October 1832, page 226.

- Last Will of James Ewing Esq. of Strathleven, enacted 1853.