The seventeenth century saw a steady expansion of Glasgow’s commerce and industry and a rash of prestigious public buildings, of church and university as well as of the city itself.

By 1707, Glasgow was second in size in Scotland only to Edinburgh. It stood alone in the beauty of its urban setting. Daniel Defoe, an agent of the Crown in the years before the Union, described it as:

“A large, stately and well built city, standing on a plain in a manner four square, and the five principal streets are the fairest for breadth, and the finest built I have ever seen in one city together. The houses are all of stone, and generally uniform in height as in front. The lower stories (of those near the Cross) for the most part, stand on vast square Doric columns with arches which open into the shops, adding to the strength as well as beauty of the buildings. In a word, ‘tis one of the cleanliest, most beautiful and best built cities in Great Britain”1.

There were around 500 merchants in a population of 12,000. It has been estimated that about 125 of them specialised in overseas trade. The pre-eminent commercial povsition of this group had been established by a Letter of Guildry from the Provost of Glasgow in 1605, which set out the constitution of the Merchants House, the organisation of overseas and domestic traders and of the Trades House, representing the craftsmen’s guilds. It set out a series of terms that defined the rights and privileges of the ‘guild brethren’ of traders and craftsmen but also set limits on the numbers wanting to join the lucrative trade in sugar and tobacco.

In practice, access to transatlantic trade was restricted to those who had the necessary financial means, colonial experience and the trading and kinship contacts. As a result, the colonial merchants were a small group from the wealthiest end of Glasgow society. They dominated the town council and influenced most aspects of Glasgow’s development. Their privileged status was reflected in their early headquarters, The Merchants Hospital.

The Merchants Hospital was situated in the commercial centre of the town, at the Briggait, near the Saltmarket. It was rebuilt in 1659, perhaps to plans by Sir William Bruce (c.1625-1710). It was typical of many of the civic buildings in Glasgow at the time, illustrating how architecture in the burgeoning urban landscape was guided by the influences of the Renaissance but blended with existing medieval characteristics.

A two-storey building, the Merchant’s Hospital was nine bays wide with a magnificent tower and clock. The axial steeple, completed in 1665, had a copper sailing ship atop a globe, instead of the usual weather cock. The steeple stands testament to the town’s links with the New World and the colonial trade which produced so much of the wealth that would make the city great.

The geographical location of Glasgow made it ideally situated for the Atlantic colonial trade. It was at the head of the main trading artery, the River Clyde, a short distance from its satellite ports of Greenock and Port Glasgow.

The rapid expansion of the tobacco trade with the Chesapeake, which straddled Maryland and Virginia, lay behind the improvement of Port Glasgow in the 1720s and the rebuilding of the harbour at the Broomielaw to accommodate larger sea-going vessels. A typical ship, laden with manufactured goods for the colonial planter class, carried twenty sailors. The round voyage lasted between six and nine months.

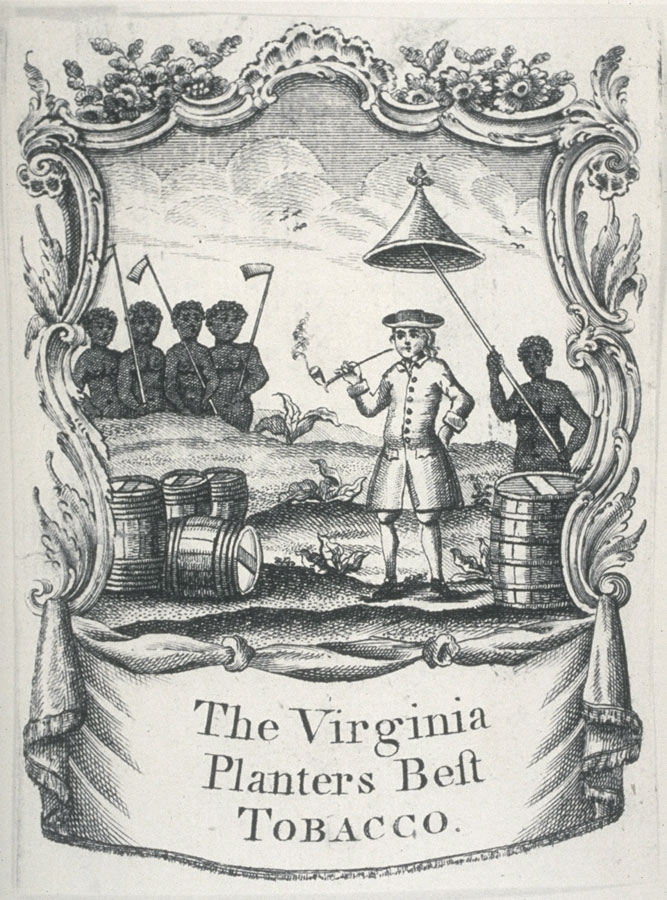

The main trading regions were Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. Unlike the Caribbean, tobacco plantations in this region were still small-scale affairs and worked by indentured servants. In 1690, only 15 per cent of the population was made up of black slaves.

Between 1700 and 1740, the economics and scale of tobacco plantations were transformed with the transportation into chattel slavery of 50,000 Africans. The harsh Barbadian Code of 1661 was adopted in South Carolina in 1696. Various slavery laws followed in different colonies, including a comprehensive code adopted in Virginia in 1705. Labour was intensive; slaves continually weeded fields, planted, tended and harvested the tobacco crop through its long growth cycle.

After 1700 tobacco quickly established itself as the most important export from the American colonies. Glasgow soon became the main market-place. Imported tobacco was rapidly re-exported to England, France, Holland and Germany. This entrepôt trade resulted in a rapid accumulation of wealth, allowing huge fortunes to be made by a small number of Glasgow merchants.

The scale of new wealth in Glasgow was unprecedented and it created a new breed of aristocracy. The ‘Virginia Dons’ dominated the public and private domain of the city for the next hundred years. The impact of the new-found wealth of merchant families such as the Bogles, Dunlops, Oswalds and Buchanans had a profound impact on the urban environment as the rapid influx of colonial wealth prompted conspicuous consumption.

Merchants displayed their new wealth and rise in social status by building large mansions, which created a new townscape in Glasgow. Those of lower social standing were crammed in tenements in the medieval heart of the town, while the colonial trading aristocracy built new, fashionable streets, often named after themselves or the colonies where their fortunes were made.

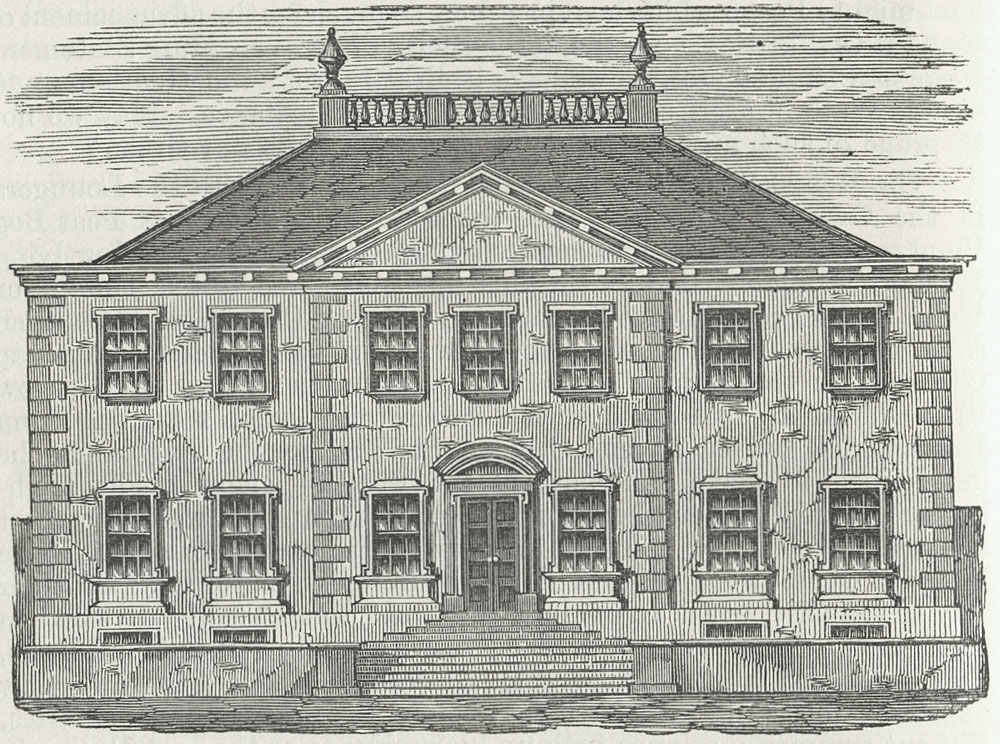

This was a new town, built in the semi-rural suburbs of the medieval settlement; begun half a century before Edinburgh’s celebrated New Town. One of its earliest buildings, the Shawfield Mansion, was built at the end of what is now Glassford Street in 1711-12 to a plan by Colen Campbell (1676-1729). This was Campbell’s first documented work. He later came to prominence in England with the publication of his Vitruvius Britannicus (1715-25) which included the Shawfield design.

The Shawfield Mansion set the precedent for a classical revival in Britain. The plot on which it was situated stretched from Back Cow Lone, now Ingram Street, to the Trongate and featured elaborate ornamental gardens. The mansion itself, a magnificent seven-bay villa, featured the pedimented centrepiece, rustication, pronounced cornice and balustrading which were all to become standard motifs.

The extravagance of the Shawfield Mansion reflected the status of its owner, Daniel Campbell (c.1671-1753), a slave trader who was one of the pioneers of the Virginia trade. Campbell was the son of a notary who became owner of several sugar warehouses and later the collector of taxes at Port Glasgow. He epitomised the city’s elite colonial merchant class.

Although the Shawfield Mansion is long gone, it left a lasting legacy in Glasgow’s built heritage as the model for the architectural style favoured by the ‘tobacco lords’. It and other grand mansions shifted the natural axis of the old town westward, testified to the status of the nouveaux riches and illustrated the enormous divisions of wealth created by Glasgow’s colonial trade.

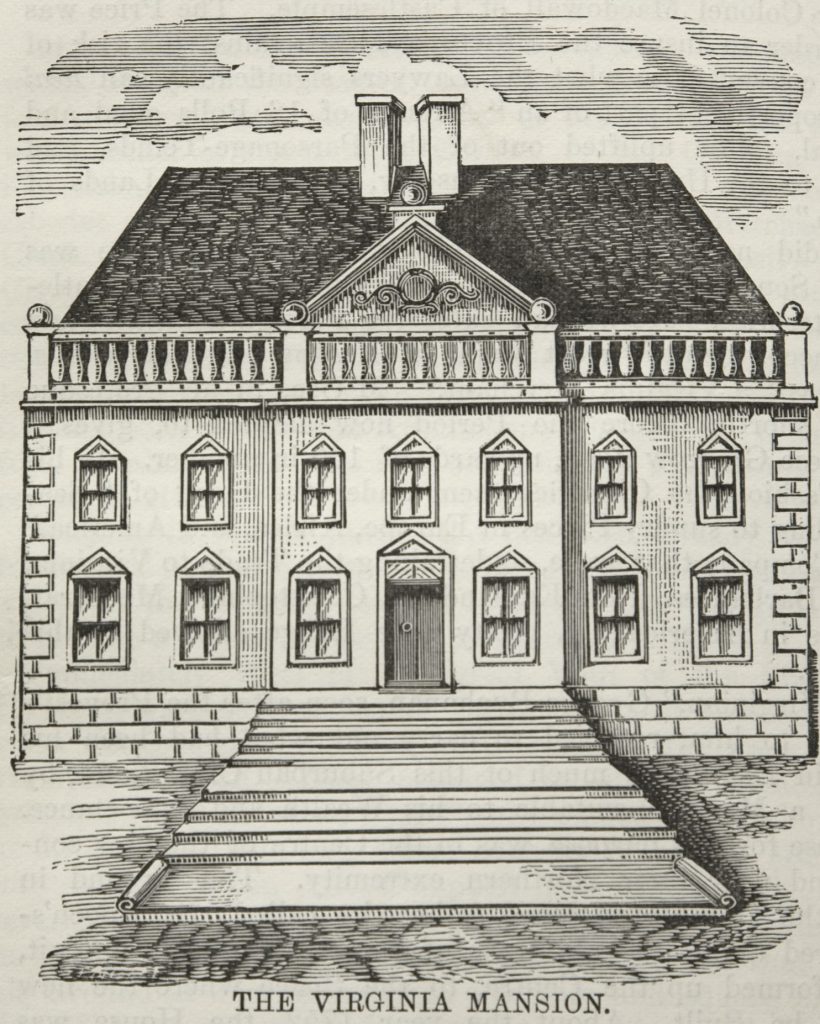

If one lost building were to be singled out as a monument to the importance of the tobacco trade it was the Virginia Mansion, which sat on the site of the modern Corinthian. Its large plot stretched from the Trongate to Back Cow Lone. Its story began with Andrew Buchanan of Drumpellier (1690-1759) one of the original Virginia Dons and twice Lord Provost of Glasgow in 1740 and 1741. He accrued the plot over a number of years, intending to build a large stately home.

Buchanan of Drumpellier was also founder, in 1730, of the largest tobacco importer in Glasgow, Andrew Buchanan Bros. and Co. which had several interests in the West India sugar trade and tobacco plantations in Virginia. Drumpellier began laying out a new street, named Virginia Street in 1752 but died before it was completed.

After Andrew’s death, his son George Buchanan of Mount Vernon (1728-62), completed the opulent mansion, in accordance to his father’s wishes. It was described as: ‘a very spacious edifice and finely proportioned’ with a seven-bay façade, obviously influenced by the design of its near-neighbour, the Shawfield Mansion.

These luxurious town-houses set a point-de-vue precedent, in locating a grand building at the head of a large avenue. This became a regular motif of the new town’s urban alignment. George Buchanan later finished laying out Virginia Street, the first completed street in Glasgow’s new town. It became the most fashionable place for merchants to reside, although far removed from the old commercial centre at the Saltmarket. The Virginia Mansion was later demolished yet the street name survives in testament to the region and trade which transformed Glasgow – and a reminder of the city’s largely unacknowledged links with slavery.

Next section:

References

- Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, 1726.