The age of agricultural ‘improvement’ went through various stages of development in eighteenth-century Scotland. The period from 1760 onwards saw sustained improvement of land on a large scale by the application of modern agricultural procedures. In the West, especially around Glasgow, this was fuelled by the influx of colonial wealth.

The tobacco lords and sugar aristocracy purchased large estates in order to consolidate their transition from nouveaux riches to landed gentry enjoying considerable political and social influence. Successful colonial traders had both the finance and the vision to have a significant impact on the improvement process.

Adam Smith (1723-1790), the father of modern economics who held the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University from 1752 until 1764, wrote in his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations (1776):

‘Merchants are commonly ambitious of becoming country gentleman and when they do, they are generally the best of all improvers. A merchant is accustomed to employ his money chiefly in profitable projects; whereas a mere country gentleman is accustomed to employ it chiefly in expence. The one often sees his go from him and return to him again with a profit; the other, when once he parts with it, very seldom expects to see anymore of it … The one is not afraid to lay out at once a large capital upon the improvement of land, when he has a probable prospect of raising the value of it in proportion to the expence’1.

In the West of Scotland, wealth accrued from trade with the New World had a marked effect on land development. Some of these landed estates eventually became parts of new suburbs as the urban sprawl moved outwards from the centre of Glasgow.

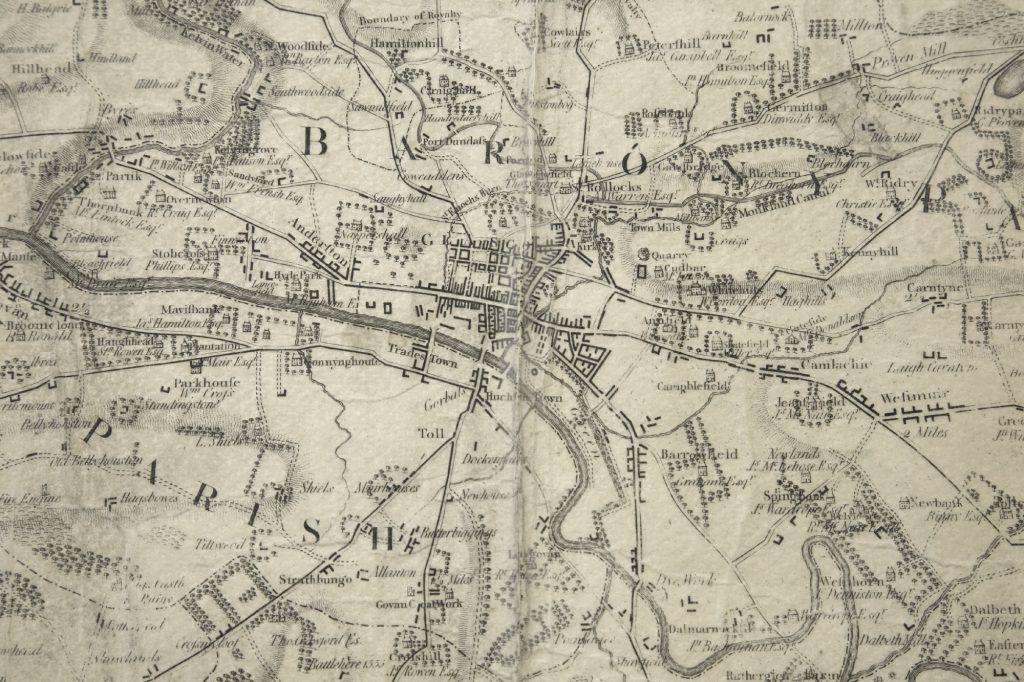

Between 1770 and 1815, approximately half of the 140 merchants in Glasgow involved in the tobacco and sugar trade owned landed estates of over 500 acres. The most prominent tobacco lords had the financial means to accumulate and keep control of land. Most of this elite group had a long-term commitment to land purchase. Estates were purchased in Glasgow, Renfrewshire, Dunbartonshire, Lanarkshire, Stirlingshire and Ayrshire.

There were economic as well as social reasons why the colonial traders sought to purchase landed estates. The colonial trade was a volatile and unpredictable business; land was an investment that could be passed through inheritance to future generations. An estate guaranteed income through rentals of plots to tenants and provided a desirable asset that could be used as security to obtain future loans. In terms of social standing, a landed estate provided a means of gentrification, opportunities for political advancement and a controlling influence in important aspects of life in the local area. In this way, merchants such as John Glassford and the Oswalds entered the landed elite whilst families such as the Buchanans consolidated their long-established position.

John Glassford, the son of a magistrate and sometime merchant from Paisley who became one of the wealthiest of the tobacco lords, purchased an estate of thirty-three acres from The Merchant’s House in 1745 and immediately built a large mansion, which he named Whitehill. This was situated in the area of what is now Duke Street in the southern flank of modern Dennistoun. Glassford later accrued the surrounding land to his estate in order to increase the value and attractiveness of the property and to lay a carriage-way for his daily journey on ‘a coach and four horses’ to the commercial centre of Glasgow.

Glassford adopted a patriarchal role in his estate: ‘He dispensed in Whitehill princely hospitality, and was universally respected’2. He sold Whitehill in 1759 and purchased the Shawfield Mansion in 1760. He eventually came to own larger estates at Balvie and Dougalston in Dunbartonshire, from which he took his title.

Glassford viewed himself as a gentleman improver, although he confessed to having little real knowledge of agricultural processes. His role as an improving landlord was a recreational, almost a leisure pursuit. Yet he spent huge sums of money on liming the soil, laying out fields and even making a cut from the Forth and Clyde Canal to transport dung to his estates.

The Buchanan’s were an established and respected family of colonial traders and had various estates around Glasgow. Andrew Buchanan, one of the original Virginia Dons and twice Lord Provost of the city, purchased the estate of Drumpellier in 1750. In addition, he increased the lands surrounding the Virginia Mansion, laying them out as vegetable gardens.

The Windyedge estate, near modern Ballieston, was added to the Buchanan investments by his brother George Buchanan (1728-1762) in 1756. He erected a large country house and planted and adorned the ground with ornaments ‘in the most tasteful manner’3. He renamed the estate Mount Vernon as a compliment to George Washington, who was a neighbour in colonial Virginia and had an estate of the same name.

After the financial crash of 1776, brought about by the American War of Independence (1775-83), both the Drumpellier and Mount Vernon estates had to be sold. However, David Buchanan (1760-1827), son of George, made his fortune trading in Virginia and came home to reclaim the family estates from trustees, a good example of colonial wealth being repatriated from the New World.

The Buchanans and John Glassford are both a lasting part of Glasgow life, with streets name in their honour. Their social standing was also marked by their burial in the exclusive Ramshorn Kirk. St David’s Church on Ingram Street, now the Ramshorn Theatre, is an early example of the Gothic architectural revival. The older Ramshorn cemetery, now partly covered by Ingram Street, was the most fashionable and expensive place to be buried in eighteenth-century Glasgow.

John Glassford was buried in the south-west corner of the cemetery. His gravestone can still be see. Andrew Buchanan was buried in the older part of the cemetery. When Ingram Street was widened to allow the passage of modern traffic, he was left interred under the street, although the family plot is close by the entrance to Glasgow Cathedral.

The Oswalds, another mercantile family who travelled to Glasgow in search of a colonial fortune, achieved high social status through titled estates and also had their standing displayed as a street name. In 1751, Alexander (1694–1766) and Richard Oswald (1687–1763), merchants in Glasgow and slave traders, bought Scotstoun, an estate of 1,000 acres. It included the lands of Balshagray to the west of Partick, stretching from the River Clyde to Great Western Road.

The Oswald family became involved in all aspects of commercial life in Glasgow and their descendants came to own landed estates. George Oswald of Scotstoun (1739-1819) nephew of the notorious Oswald of Auchincruive, was a tobacco lord and later Rector of the University of Glasgow. His brother Alexander Oswald (1738-1813), one of the founders of the Royal Infirmary, was part of a new type of merchant landlord – land speculators who bought and sold landed estates. He purchased Langlands in Govan in 1782 and rapidly sold it on to James McCall. Oswald epitomised the great mercantile family, yet attempted to distance himself from the brutalities of slavery through the repatriation of colonial wealth.

Other merchants such as Archibald Smith of Jordanhill owned estates close to the centre of the town which rose sharply in value as the urban spread west gathered pace. The building boom of the late eighteenth century owed much to mercantile land investment.

The younger Alexander Oswald’s own business was chiefly bound up with colonial trade. He purchased the Shield Hall estate in 1781. Shield Hall was in the parish of Govan, about four miles from Glasgow Cross. The estate extended to more than 300 acres and consisted of smaller properties, described as ‘bonnet lairdships’4. His perception of himself – as a rural landlord, a man who inherited vast colonial wealth, and the owner of sugar houses in Glasgow – is revealing:

‘But from the leading business of the day he held aloof. He had tempting West Indian offers, but he refused them all: he would not, directly nor indirectly, mix himself up with slavery’5.

Here was a tobacco lord whose purchase of landed estates was part of an effort to distance himself from the slave trade. Gentrification was part of the process of calculated detachment from plantation economics. Increasingly, involvement in the sugar and tobacco trades was acceptable but dealings in slavery itself were not.

The expansion of mercantile estates in the Glasgow area was also a factor in the origins of heavy industry. Shrewd investors purchased land to exploit its mineral resources. James McCall’s estate at Belvidere near the town centre was described in 1798 as laden with coal. The Jordanhill estate provided a rental of £500 per annum from coal royalties.

A good example of links between colonial commerce, land purchase and the domestic economy was James Dunlop, who became one of the leading coal masters in Scotland. From 1783 onwards, he purchased a series of estates within travelling distance of Glasgow which had resources of iron and coal. The growing need for coal in Glasgow was supported by the development of the Monkland and Forth and Clyde canals, which became the most important means of transportation.

Adam Smith was in no doubt, when he wrote The Wealth of Nations, that colonial commerce and related industries were the main cause of the age of ‘Improvement’:

‘It is thus that through the greater part of Europe the commerce and manufacture of cities, instead of being the effect, have been the cause and occasion of the improvement and cultivation of the country’.

The long-term impact of colonial wealth on both the ‘Improvement’ of Scotland and the development of Glasgow remains a controversial issue.

A modern form of denial suggests that merchants transferred most of their colonial wealth into large unproductive ventures in their palatial country estates, with minimal long-term effect on the development of Scotland. Yet, the majority of colonial traders who owned land were concentrated around Glasgow. Many of them owned estates which did prove profitable in the longer term. New World money brought urban settlement, suburbs and rural hinterland together in new and often significant relationships. With it came the emergence of a ‘greater Glasgow’.

Next section:

References

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776 p259.

- J. Smith and J. Mitchell, Whitehill House in The Old Country Houses of the Glasgow Gentry, 1878.

- G. Stewart, The Buchanans of Drumpellier and Mount Vernon in Curiosities of Glasgow Citizenship, 1881.

- J. Smith and J. Mitchell, Shield Hall in The Old Country Houses of the Glasgow Gentry, 1878.

- J. Smith and J. Mitchell, Shield Hall in The Old Country Houses of the Glasgow Gentry, 1878.