The apprenticeship scheme in the West Indies was promoted as a major step towards putting an end to the horrors of the past. In reality, it was chattel slavery by another name.

The Scottish campaign continued, in the process evolving into a truly international movement. From 1833 onwards it was represented as a world-wide moral crusade against the countries that still practised slavery. However it was characterised by disunity, especially in its relations with American societies and in domestic conflicts over methods, tactics and the role of women campaigners. Even so, Scots continued to play a key role and Glasgow became the nerve-centre of the British anti-slavery movement.

The Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society remained influential in the continuing fight against slavery. Dr Ralph Wardlaw (1779-1853) opened his West George Street chapel to anti-slavery meetings. It was there that the young David Livingstone (1813-73), future African missionary, listened intently to his sermons.

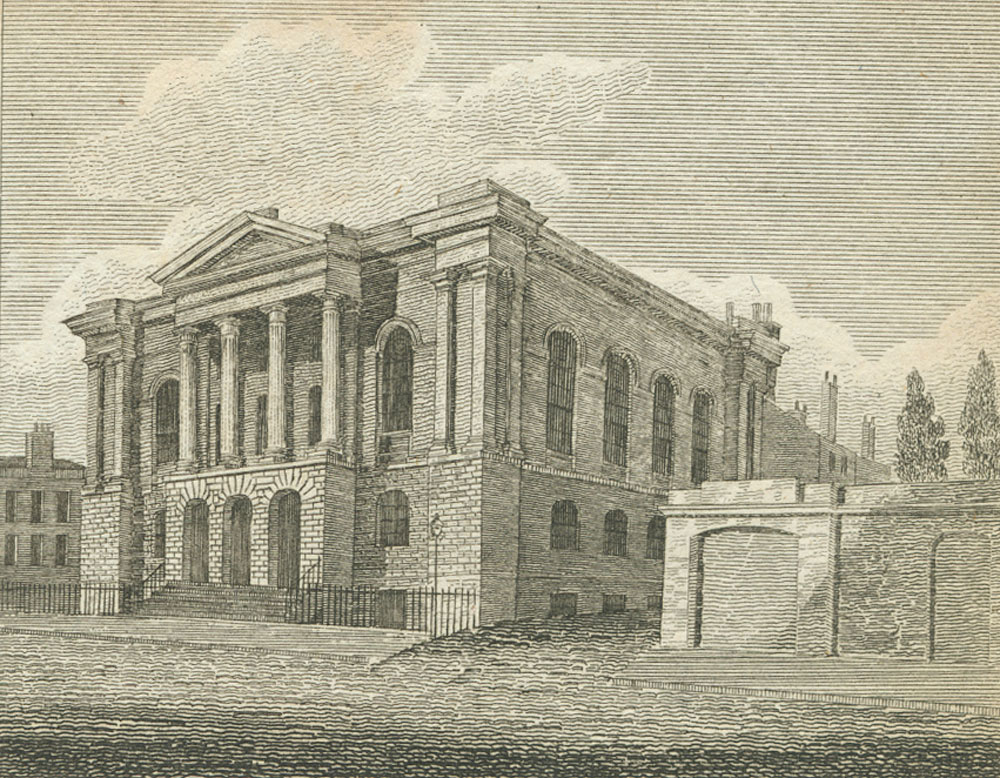

The West George Street Chapel, which could hold over 1,500 people, sat just south of the modern Queen Street railway station. It was designed by James Gillespie Graham (1776-1855) and constructed in 1818 at a cost of £10,000 for the Congregational Church. The building was elaborate, with a Roman Doric portico and fluted pilasters. Its distinctive classical architecture differed sharply from the contemporary predeliction for Gothic, for reflecting the Congregationalist’s dissenting stance, critical of the concept of an established or national Church. Sadly, the Chapel was demolished in 1975.

Wardlaw would become one of the leading abolitionists in Britain. He was Vice-President of the Glasgow Emancipation Society, formed in 1833 with the aim of abolishing global slavery but with a particular focus on the USA. This was, in effect, the Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society with a new direction. Other leading founder members included William Smeal (1792-1877) and the African-American James McCune Smith (1813-65).

The story of McCune Smith is a further illustration of the anti-slavery stance of Glasgow University. He completed a bachelor’s degree in 1835, a master’s degree in 1836, and a medical degree in 1837, his studies perhaps in part funded by the Glasgow Emancipation Society. He was the first African American to graduate M.D. in the world and the first to practice medicine in America. The Glasgow Emancipation Society maintained close contact with him and the American Anti-Slavery Society after his return in 1837 to New York, where he became a prolific writer and campaigner for emancipation.

Glasgow University alumni made a unique contribution to the abolitionist movement, which was vastly influential and remains largely unknown and certainly not officially recognised. The literary critiques of Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith and John Millar influenced the development of anti-slavery societies globally and provided leading abolitionists with the knowledge to attack the practice of slavery.

Adam Smith was friendly with William Pitt the Younger who, as Prime Minister, introduced the Bill to Abolish the Slave Trade in Parliament. Pitt consulted Smith on economics and introduced him to William Wilberforce. At one meeting, the two British statesmen refused to sit down before Adam Smith as a mark of respect, stating:

“No, we will stand till you are first seated for we are all your scholars.”1

Thomas Clarkson, the remarkable propagandist, was in no doubt about the influence of Hutcheson, Smith and Millar when he stated:

“It is a great honour in the University of Glasgow that it should have produced, before any public agitation of this question, three professors, all of whom bore their public testimony against this cruel trade.”2

In spite of the vested interests of local merchants, the anti-slavery critique put forward by these three brave thinkers directly challenged the very foundation on which the tobacco and sugar trades rested. The Old College was an intellectual fortress which created an unconstrained environment allowing these critiques to flourish. This was the beginning of the end of chattel slavery in the British Colonies.

The first rays of abolitionist light that began in 1730 were passed from mentor to protégé; Francis Hutcheson to Adam Smith and Smith to John Millar. A Glasgow University triumvirate of John Millar, John Young and Patrick Wilson drafted one of the first abolitionist petitions from Scotland in 1788. Young maintained his strong opposition to slavery and passed the torch to his pupil Ralph Wardlaw, when he taught him in the University in 1796. Master and pupil became lifelong friends and confidantes on ecclesiastical matters.

Wardlaw represents the culmination of a tradition at Glasgow University that continually opposed the evils of slavery. It is extraordinary to consider that the torch of abolition lit by Hutcheson was finally passed via Wardlaw to David Livingston in the West George Street Chapel.

The Glasgow Emancipation Society focussed its endeavours on the apprenticeship scheme. Journal accounts showed that the six-year transitional period had improved little. Indeed some have regarded this period as ’worse than slavery’. The Society used the same tactics as in previous campaigns – mass petitioning and lectures by influential speakers.

Petitioning was particularly effective: in 1836, almost 30,000 Glaswegians signed a petition condemning the apprenticeship scheme. One of the key supporters of this campaign was James Oswald (1779-1853), one of the two M.P.’s for Glasgow after the Reform Act of 1832. He was a nephew of Richard Oswald of Auchincruive, who half a century before was still transporting thousands of Africans into chattel slavery from Bance Island. The Oswald family had travelled full circle, from colonial merchants and slave traders to abolitionists. That journey – and the status of Glasgow as a leading abolitionist city – is symbolised by the striking statue of James Oswald by the Italian sculptor, Baron Marochetti (1805-67) in George Square, erected in 1855.

The City Chambers loftily overlooking Oswald’s statue is a striking symbol of Victorian Glasgow’s claim to be the second city of the Empire. One of the most impressive buildings in Scotland, it was designed by the London architect William Young and completed in 1890. Its grandeur reflects what was then the most powerful empire in the world. On the topmost pediment on the main façade, the statue of Queen Victoria is flanked by native peoples bearing gifts from the Empire. It is deeply symbolic of the subservient relationship of colonial peoples, long the very foundation stone of the British Empire.

These images from George Square symbolise both the central role taken by Glasgow in the colonial and slave trades and the unique part it played in the destruction of slavery. By 1838, societies across Scotland had organised as many as 373 petitions to Parliament: the de-construction of the apprenticeship scheme was underway.

The Oswald petition was followed in April 1838 by another organised by the Glasgow Emancipation Society. The growing level of protest is illustrated by its staggering number of signatories – 102,200. The apprenticeship scheme was finally abolished by Parliament a month later, in May 1838.

Despite the broad consensus of rejection across Scotland, elected M.P.s did not offer the same level of support for the abolition bill. It is a recurrent theme throughout the period, that popular rejection of slavery lacked backing from the political and social elite. Of course, the motivating factor was finance.

The end of the apprenticeship scheme signalled the end for the West Indian apologists in Glasgow and marked a new phase in the abolitionist movement. Its focus was now outwards, directed particularly towards America. By now the British campaign was virtually controlled by societies in Scotland. Ralph Wardlaw saw the Scottish movement, now unchecked by West Indian interests, as an act of atonement for national sins.

The enthusiasm of Scots abolitionists was that of redemptionists: the cleansing of a nation tainted by colonial wealth – and Glasgow led the way. The movement became truly international, not only in it’s aims but in it’s methods; as various influential speakers, including black abolitionists, came to Glasgow to deliver key speeches.

Although their role has been largely unacknowledged, for the first time women became prominent in the movement. There were sixteen Ladies Abolition Societies established in Scotland between 1833 and 1868, with the strongest in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Around 162,000 women in Edinburgh signed an abolition petition in 1833. In Glasgow, women were equally active.

The Ladies Emancipation Society was formed by Jane Smeal, daughter of William Smeal, a Quaker tea merchant who was also a prominent abolitionist. She became a leading figure in the British movement. Jane described the involvement of Glasgow women to a prominent English abolitionist in 1836:

“The females in this city who have much leisure for philanthropic objects are I believe very numerous – but unhappily that is not the class who take an active part in the cause here – neither the noble, the rich, nor the learned are to be found advocating our cause. Our subscribers and most efficient members are all in the middling and working classes but they have great zeal and labour very harmoniously together.”3

Their tactics were very similar to the male societies – mass petitions, pamphlets, public meetings and lectures by prominent abolitionists.

At the time, women’s involvement was controversial. Wilberforce had viewed women merely as providers of emotional support. The ’Woman Question’ was still on the international abolition agenda in 1840, when the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention met in London. Female abolitionists from Scotland and America were at first refused entry. A shameful compromise allowed prominent female campaigners, some of whom had travelled over 3,000 miles, to view the proceedings from the gallery. The passion and commitment of women abolitionists set the tone for future campaigns – most notably the suffrage movement in the early twentieth century.

Glasgow became the global vanguard of abolition and internationally famous campaigners came to deliver speeches. Arguably the most famous of all, Frederick Douglass (1818-95), who had himself escaped from slavery in 1838, came to Scotland in 1846 during a two-year lecture tour around Britain. He returned in 1860. In 1845 he published the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a vivid account of life in the South which quickly became a best-seller.

Douglass had a particularly warm affection for Scotland; he felt safer here than at any other time in his adult life and did not endure as much prejudice as he did in America. It was fitting that British anti-slavery societies collected money to buy Douglass out of slavery and, in a symbolic gesture, he was officially freed in December 1846. He delivered his famous ‘Send Back the Money’4 speech at City Halls in Albion Street in January of the same year, condemning Dr. Thomas Chalmers and the Free Church for accepting a donation of £3,000 from the American Presbyterian Church, whose congregation was substantially made up of American slave owners.

Douglass’ advocacy provided a central theme for anti-slavery lectures across Scotland, including Glasgow, Paisley and Dundee. Yet the ‘Send Back the Money’ campaign almost bankrupted the Glasgow Emancipation Society and it widened existing divisions amongst anti-slavery societies in Scotland. The City Halls, designed by George Murray and completed in 1841, was the first performance venue in Glasgow. It became a focus for events ranging from orchestral concerts to political rallies and anti-slavery meetings. This venue is a further illustration of Glasgow’s truly international contribution to the abolition movement.

The City Halls were also the venue in 1853 for a lecture by a quiet American housewife, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-95). The event was organised by the Glasgow New Association, an emancipation group fronted by the African American abolitionist J.W.C. Pennington. Stowe was the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, contributing a sentimental narrative to the movement which nonetheless helped to highlight the issues around slavery as never before.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold over one-and-half-million copies. When Stowe visited Great Britain in late 1853 over half-a-million people signed the welcoming address to her lecture tour. The Glasgow New Association started up the Uncle Tom’s Offering to make up the royalties that Mrs Beecher Stowe was unable to receive in Britain. A later guest of the Association was Rev. Josiah Henson (1789-1883), a slave who had escaped to Canada in 1830 and was the inspiration for the fictitious ’Uncle Tom’. He was given a civic reception in the City Halls in 1877.

By the time of Henson’s visit, slavery in the USA had been abolished. The level of commitment of the later abolitionist movement in Scotland, especially in Glasgow, was a hugely significant factor in promoting an international conscience and an unprecedented focus on the horrors of slavery in the New World. Glasgow’s role in ending the American trade was a final act of redemption for a city which had grown rich on the profits of slavery.

References

- A. Webster, The Contribution of the Scottish Enlightenment to the Abandonment of the Institution of Slavery, European Legacy, 2003.

- Thomas Clarkson, The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, 1808 p65.

- Jane Smeal to Elisabeth Pease, 1836, quoted in Gender in Scottish History Since 1700, 2006 p55.

- N. Brown ‘Send back the money!’ Frederick Douglass’s Anti-Slavery Speeches in Scotland and the Emergence of African American Internationalism, nd.