The process of change in eighteenth-century Scotland, the ‘Age of Improvement’ or the ‘Age of the Enlightenment’ was about much more than cultural advancement, agricultural reform or theoretical ideas. The term ‘Improvement’ was used by Scots of the period in connection with a national programme for the moral advancement of society.

‘Enlightenment’, not a word used by many at the time, came to define the way in which people thought and, more importantly, dealt with their fellow beings. Although part of a wider European movement, the Scottish Enlightenment was in many ways unique. It drew on French thought by promoting the fundamental importance of science, reason and civilisation over religion, unreason and barbarity. Reason was applied as a balm to ease the anxieties of a restless society. Eighteenth-century Glasgow was at once the spiritual home of much of this new thinking yet still a major investor in chattel slavery. Nonetheless, the city’s economic transformation was matched by an equally significant ethical revolution.

The rapid growth of Glasgow, based on the New World carrying trades, created a town with a dynamic urban culture. The commercial ethos that had made many individuals wealthy pervaded the town’s social scene. It is ironic that this urban setting contributed to the development of an intellectual environment that attacked the very foundation on which colonial trade rested. Glasgow became the architect of the campaign to rid the British colonies of chattel slavery.

Glasgow University, then known as Old College, provided much of the dynamic for the spread of enlightened thought in the west of Scotland. Founded in 1451 by papal bull, it was situated from early in its evolution on the High Street, in the heart of the medieval city. Its early history is interwoven with the Cathedral. The Bishop (later Archbishops) of Glasgow, had control of both institutions. Sadly, the very sizeable building on the High Street was lost when the university relocated in the nineteenth century.

Glasgow University was no ivory tower. Its position on the High Street helped foster strong connections between commerce, merchants and Old College. Many of the sons of the tobacco lords matriculated before embarking on the ‘Grand Tour’ through Europe. In the age of the tobacco lords, the University became almost synonymous with the abolition movement in Scotland, as leading Enlightenment figures, based in Glasgow developed a sustained critique of slavery which inspired campaigners on a global scale.

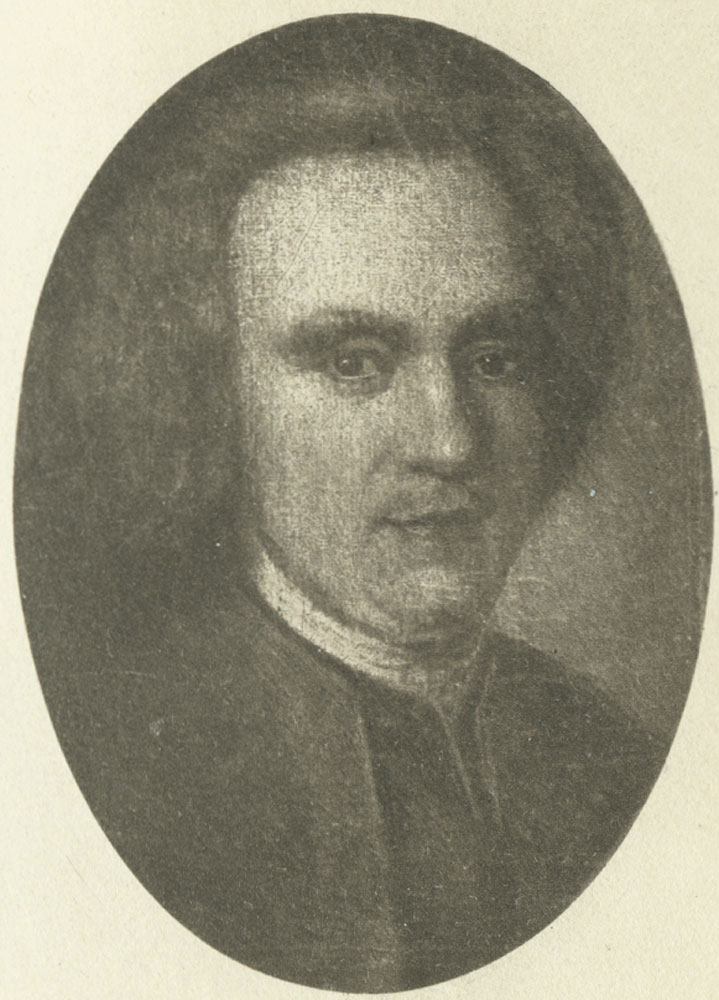

Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), although born in Ulster, the son of a Presbyterian minister, had strong Scottish links. He was descended from Scottish emigrants and spent his formative years at Glasgow University from 1710 until 1718. After teaching and writing in Dublin, he returned to his alma mater in 1730 to take up the chair of moral philosophy. Sometimes called the ‘founding father of the Scottish Enlightenment’, Hutcheson set out a powerful account of human nature in his most influential work, A System of Moral Philosophy (1755). At its core was a belief in universal natural rights and the equality of all men:

“This state of natural liberty obtains among those who have no common superior or magistrate, and are only subject to God, and the law of nature”1.

Hutcheson’s critique of slavery did not stop at criticism of the forms prevalent in ancient Greece and Rome. He rejected both the Classical view that ‘some men are naturally slaves’ and contemporary justifications of chattel slavery which treated slaves as inherited property, which could be inherited across generations: ‘No damage done or crime committed can change a rational creature into a piece of goods void of all right, and incapable of acquiring any, or receiving any injury from the proprietor’2. His opposition to the rule of unjust governments was, by extension, a wholesale critique of colonial rule. On the other hand, much like Fletcher of Saltoun, he conceded that some individuals in society, such as the idle, might be subjected to a form of indentured servitude as punishment.

Hutcheson’s philosophical opposition to slavery was clearer and less ambiguous than that of his influential French contemporary Montesquieu (1689-1755). Yet Hutcheson’s view, though first propounded fiercely in the lecture halls of Glasgow University, probably had greater impact after his death, amongst his celebrated protégés. His work, though written years previously, was published in 1755, nine years after his death. It was printed by the famous Foulis Press in Glasgow.

Robert Foulis (1707-76) and his brother Andrew Foulis the elder (1712-75) were both born in Glasgow and attended the University. Robert matriculated in 1730 to study moral philosophy under the influence of Hutcheson. It was not for an academic career, however, that they are best remembered, but as the printers of the Glasgow Enlightenment. Robert Foulis was encouraged by Hutcheson to become a classroom tutor and from 1740 a printer, based in the University.

The Foulis brothers were formally appointed printers to the university around 1743 for classical works and class texts. Their output was prolific: over 600 editions of classical texts, including Greek and Latin epics. The influence of Hutcheson on their publications was considerable; he provided funds and the Foulis titles were consistent with his own values. He and Robert maintained a close personal relationship and some forty separate editions of his own works resulted.

The Foulis brothers later established an academy of fine arts which was supported by Glasgow University, whilst the tobacco lords, John Glassford and Archibald Ingram, provided financial support. It was a member of the academy, Archibald McLauchlan, who painted the famous portrait of John Glassford and his family in the Shawfield Mansion around 1767.

Both Foulis brothers were buried in the old Ramshorn Kirk graveyard and remained interred when Ingram Street was later widened. A cross with the initials RF and AF marksthe spot where they were buried under the modern pavement. Their legacy remains. The Foulis Press and Academy were the foundation stones of the Glasgow Enlightenment and the vehicle that exported Frances Hutcheson’s moral ideals to Europe and America.

It was another Hutcheson pupil who attacked the concept of slavery from a different perspective – the economics of slave plantations. Adam Smith (1723-90) was born in Fife but travelled to Glasgow at the age of fourteen to matriculate at the university, where Frances Hutcheson was a tutor. Smith later attended Balliol College Oxford and returned to Glasgow as Professor of Logic in 1751.

Smith taught at Glasgow until 1764 where he lectured under four broad themes. Two of these themes provided the basis for Adam Smith’s classic texts – ethics, printed as A Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and concerning the riches of governments, which became his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations (1776).

Smith’s publications were certainly influenced by the Hutchesonian ideal. He succeeded his mentor in the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow and as the leading Enlightenment thinker, opposing the concept of slavery. Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments made it clear that it was immoral ‘to reduce them into the vilest of all states, that of domestic slavery, and to sell them, man, woman, and child, like so many herds of cattle, to the highest bidder in the market’3.

Adam Smith was an opponent of slavery yet at the same time maintained good relations with many Glasgow merchants. He was a leading member of various clubs, such as the Glasgow Literary Society, where he lectured on commercial and economic matters. His close personal friend was the tobacco lord and Lord Provost of Glasgow, Andrew Cochrane of Brighouse (1693-1777), who provided Smith with evidence from the tobacco plantations for The Wealth of Nations. Adam Smith’s masterwork advocated free trade, a ‘system of natural liberty and justice’ and provided an influential economic critique of slavery:

“From the experience of all ages and nations, I believe, that the work done by free men comes cheaper in the end than the work performed by slaves. Whatever work he does, beyond what is sufficient to purchase his own maintenance, can be squeezed out of him by violence only, and not by any interest of his own”4.

Smith was appointed rector of the university in 1787. He regarded this period as the happiest of his life. He died in 1790 and was buried in Edinburgh’s Canongate kirkyard. His work remains influential even today and he is widely regarded as the father of modern economics. His anti-slavery rhetoric was much quoted by the abolitionists, to demonstrate that a ‘moral economy’ in Britain could not be based on chattel slavery. There can be little doubt that the philosophical challenge to slavery in the British colonies originated in Glasgow, in the teachings of Hutcheson and Smith.

This staunch challenge was later given legal foundation when it was legitimised in a famous Scottish court case in the same period. Joseph Knight, an African slave born in Jamaica around 1753, was brought to Scotland by John Wedderburn in 1768 and employed as a personal servant on his estate at Ballindean, near Perth.

Knight assumed that he was employed as an indentured servant and would be freed within seven years. In the meantime, he adapted to the new surroundings. He was baptised a Christian, married a servant girl and learned to read and write. In 1772, the famous Somerset judgement in England, which freed a former slave, was published in an Edinburgh newspaper. Knight took the case to be a national ruling which justified the end of his indenture.

Knight left for Dundee to live with his wife but was promptly arrested and taken before the courts at Ballindean in 1773. The ruling supported Wedderburn’s claim to have a right over Knight for life. However, an appeal at Perth Sheriff Court rebutted this claim by passing a ruling that stated:

“The state of slavery is not recognised by the laws of this kingdom, and is inconsistent with the principles thereof: that the regulations in Jamaica, concerning slaves, do not extend to this kingdom; and repelled the defender’s claim to a perpetual service”5.

John Wedderburn appealed this decision before the Court of Session where the case was heard in 1778 before a full panel of judges, including the leading Enlightenment figures, Lord Kames and Lord Monboddo. Knight had some support and his legal counsel was paid by sympathisers: ‘some gentlemen in Glasgow have subscribed £500 for supporting the Negro’.

The Perth decision, that Knight could not be sent back to Jamaica against his will, was eventually upheld by a majority decision but the result was not as clear-cut as has sometimes been suggested. The twelve law lords produced almost a dozen different opinions. One held that Knight was ‘our brother although not of our colour’. Three others judged that Knight was thirled to Wedderburn for life, without a right to wages. Whatever the outcome of the case, it goes too far to claim, as some have, that the principle of ‘No Slavery in Scotland’ was established almost thirty years before the British parliament condemned slavery in 1807.

Opinions in society as a whole remained as divided as those of the law lords. Henry Dundas (1742-1811), Lord Advocate and M.P. for Midlothian and later Rector of Glasgow University, delivered a powerful speech on Knight’s behalf:

“Mr Dundas’ Scottish accent, which has been so often in vain obtruded as an objection to his powerful abilities in parliament, was no disadvantage to him in his own country. And I do declare, that upon this memorable question, he impressed me, and I believe all his audience, with such feelings as were produced by some of the most eminent orations of antiquity. This testimony I liberally give to the excellence of an old friend, with whom it has been my lot to differ very widely upon many political topics; yet I persuade myself, without malice, a great majority of the lords of session decided for the Negro”6.

Yet Dundas later delayed the Act to abolish the slave trade. Lord Monboddo, one of the appeal judges, owned a black slave in his personal service, whilst Lord Kames (1696-1782), a leading figure in the Enlightenment who supported Knight, stigmatised Africans as racially inferior in Sketches of the History of Man (1774). The Joseph Knight judgement was heavily qualified and fell short of a general statement on slavery. It also summed up the feelings of much of society as a whole.

Knight was not alone. Slaves in Glasgow were not uncommon. In 1763, a slave called Ned Johnston escaped from his master, Archibald Buchanan of Glasgow, alleging that he had been subjected to brutal beatings. Magistrates in Glasgow freed him from his misery. William Colhoun worked as a chief mate on ships that travelled from Britain, North America and Africa between 1768 and 1776. He sent various letters to his brother-in-law and his sister, Miss Betty Colhoun, who lived near the Trongate. The letters described the daily life of a Glasgow sailor, including his position on slave ships. He described his feelings towards his young slave girl when he wrote to his brother in law from Sierra Leone in April 1775:

“Sir, I have a very fine girl about 12 years of age. I have had her eighteen months with me. She is very smart and will learn anything that is shown her. I have a great regard for the girl and I don’t mean to sell her if my sister Betty will accept her I shall send her home, she can speak good English and I was the first white man she ever saw. If Betty will not have her you may ask Janet if she will be of any service and she shall have her. If not, I know not what to do with her as I shall never sell her. She has been more service to me than any white woman that I ever knew except my mother. If it please God to spare me my life for two or three years until I come home she will be more careful over me in my old age than any white I can get”7.

There is evidence to suggest that there were around seventy black slaves in eighteenth-century Scotland, brought from the tobacco and sugar colonies in the Caribbean and Virginia and ‘employed’ in personal service. The Colhoun letters highlighted the accepted practice of employing transported children as servants, whilst the Glassford family portrait illustrated that this was not uncommon in Glasgow.

The famous painting of John Glassford (1715-83) and his family was painted by Archibald McLauchlan around 1767 in the exquisite setting of the Shawfield Mansion. It depicted the shadowy figure of a young black servant, a symbol of wealth and status at the time. Although some accounts have suggested that the child was later painted out by the Glassford family in the abolition era, recent restoration work at the People’s Palace discovered the image had faded only as a result of discolouration of the pigment. The historic role of Glasgow in the business of slavery can be viewed metaphorically in the painting: always present yet obscured from the gaze of society through the years.

Next section:

References

- Francis Hutcheson, A System of Moral Philosophy, 1755 p10.

- Francis Hutcheson, A System of Moral Philosophy, 1755 p300.

- Adam Smith, A Theory Of Moral Sentiments, 1759 p28.

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776 p99.

- Knight v Wedderburn, 1777.

- James Boswell and John Wilson Croker, The Life of Samuel Johnson, 1823 p137.

- Colhoun (Colquhoun) of Glasgow family papers, 1776